The idea of separation of church and state remains strong in America but it is hanging by a thread, Anthea Butler said this week on NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

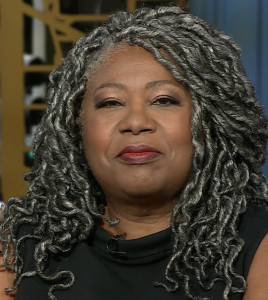

“The idea of it is very strong. The reality of it is not,” said Butler, chair of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Among Trump Republicans in particular, “I would say that the separation of church and state is very thin, if not nonexistent.”

Asked where is the line between appropriate religious expression and Christian nationalism, Butler said: “The line becomes when people become so dogmatic that they want to step over into a violent space. And what I mean by that is the people who want to impose something on someone else.

Anthea Butler

“One of the great things about America is that it’s a democracy, right? And that America got started by people who were escaping religious (persecution) so they could have religious freedom. And so one of the things I think is really important here in the delineation between what is Christian nationalism and what is not Christian nationalism is what are people trying to impose? Are they trying to use their Christian nationalism to do a takeover? And then finally, who gets to be included as a Christian in America.”

Butler joined a panel discussion with NBC News correspondent Anne Thompson; Andrew Whitehead, professor of sociology at IUPUI in Indianapolis; and former Republican Congressman Carlos Curbelo of Florida who now works as an NBC political analyst. Their topic was the rising threat of Christian nationalism.

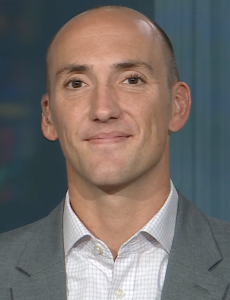

Anne Thompson

Thompson was asked if it’s possible journalists like her are making too much of Christian nationalism, if it might be hyped too much.

It’s not overblown, she said. “There are people out there who want to take the country back to a more Christian culture., I don’t think we’re making too much of it. It certainly is a strong movement. You see it in our politics today. Will it have legs? It seems to.”

Whitehead was asked if there are degrees of Christian nationalism.

Andrew Whitehead

Yes, he said, “when we survey the American public, we find that Christian nationalism is really a spectrum, where you have Americans on the very upper end who strongly embrace these ideas that the U.S. is a Christian nation, that it plays a special role in God’s work in the world globally, all of those things. And then you have Americans that think Christianity should play a role in American society but wouldn’t go so far as to say it should be privileged. And then we find there are many Americans that resist and reject Christian nationalism as well.

“And so the important thing is that it’s not a binary either left or right, but it’s a spectrum of belief and strength.”

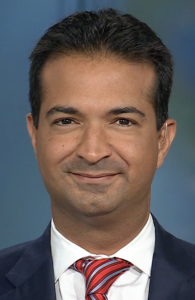

Curbelo was asked to explain what’s going on inside today’s Republican Party related to Christian nationalism. Specifically, he was asked to respond to a statement by Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, who said he’s not going to run from the label of “Christian nationalist.” And he was asked about a statement by U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who proudly claimed the Republican Party is the party of Christian nationalism.”

Carlos Curbelo

“What (you’re) pointing out is the hypocrisy in all of this,” the former Republican congressman replied. “It has been Republicans and conservatives over the years who have criticized other countries like Muslim countries for imposing religious beliefs and practices, and also for attacking communist countries for imposing atheism and banning people from practicing their religion.

“So what’s happened here is this has become a part of the culture wars. And this is the bunker mentality that Donald Trump and other conservatives have pushed a lot of the population into thinking they’re under assault.”

While Christian nationalism may be wrong and dangerous, it is fed by the reality that conservative Americans feel like “the pace of cultural change in our country has been pretty rapid in recent decades,” Curbelo added. “We have to understand that some people increasingly feel excluded, left behind, and obviously that generates a lot of anxiety and that’s why people act out in these ways.”

Whitehead affirmed that description. “When we look at it, Christian nationalism … is about power. And when we think of that in terms of a democracy and a functioning democracy, it’s about sharing power and playing by the same rules. And so with Christian nationalism, we find over and over that if it comes down to democracy or power, they’re going to choose power every time.”

But what may be a winning strategy for Republican primaries could prove to be a liability in a general election, Curbelo said. “This could be part of the trap Republicans have set up for themselves where they elect the most ‘conservative’ candidate at primaries and then these people just can’t win.

“So eventually this movement will likely just be extinguished because people get tired of losing. That’s one theory, but certainly, … there is a critical mass support that can get these people past primaries.”

Butler offered an urgent warning: “If we don’t pay attention to this right now, we may be on the losing end later. … The GOP has had slogans like this a long time, whether it’s been Make America Great Again, or American exceptionalism. … What is more interesting right now is that the religious and the political are being put together. And that makes for a very powerful mix. Whether or not people win in November, we still have to contend with this in 2024.”

Related articles:

Christian nationalism is a danger to our nation | Opinion by Marvin McMickle

Georgia representative says Christian nationalism actually is a good thing

No, BJC has not become a leftist mouthpiece | Opinion by Mark Wingfield