After having what will one day be recognized as a Hall of Fame NFL career, Demaryius Thomas died unexpectedly of what police are calling “a medical issue” in his Georgia home on Dec. 9, 2021. He would have turned 34 on Christmas Day.

As we remember the life and grieve the loss of Thomas, we also should reflect on the contrasts between his story and the story of the other first-round draft pick for the Denver Broncos in 2010 — Tim Tebow.

That year, the Broncos ended up with two first-round draft picks whose stories would give a glimpse into the evangelical culture wars that historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez later would say “corrupted a faith and fractured a nation.”

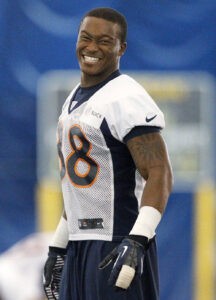

Denver Broncos wide receiver Demaryius Thomas jokes with teammates as they stretch before drills at NFL football training camp in Englewood, Colo. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

With the 22nd pick, the Broncos selected Demaryius Thomas from Georgia Tech, a shy and quiet wide receiver.

Three picks later, the Broncos selected quarterback Tim Tebow, who already had amassed a cult-like following among evangelicals during his years playing for the University of Florida.

While both these first-round picks identified as Christians, their stories and their popularity among evangelicals could not have been more different.

Darren McKee, who has been a host on Denver Sports Radio 104.3 The Fan for the past two decades, told Baptist News Global, “Demaryius Thomas was painfully shy when he arrived in Denver. He wasn’t a vocal guy in terms of rah rah. He admitted that himself. Tebow was a national celebrity when he arrived in Denver. Thomas wasn’t.”

Looking back, it seems many white evangelicals missed the depths and greatness of Thomas because they were so fixated on how Tebow made them feel about themselves.

A story of drugs and deep loss

When Demaryius Thomas began to realize that his mother and grandmother were involved with selling drugs out of their house in Montrose, Ga., he began to fear what the future might hold for them.

His grandmother Minnie Thomas told the Denver Post, “I mostly did it to make ends meet, to buy my kids what they wanted, so they could wear what the other kids were wearing, so I could keep my house nice on the inside.”

Thomas remembered, “I knew my grandma was selling it and my mom was keeping some money. I told my mother one time that they needed to stop because I had a dream that they got in trouble. I started crying like every night after then. And then it finally happened.”

Thomas described his mother’s arrest in a story for The Players Tribune: “I was sleeping by the door when the men busted in. It was 7:00 in the morning, right before school. The first thing I saw were the guns pointing at me. Big guns. Like in a movie. I didn’t know they were police. I just saw guns and red dots flashing. … I laid on the floor and they went into my mom and stepdad’s room. They brought them out in handcuffs. As they were walking my mamma to the police car, she said, ‘Can I please just take my kids to the school bus one last time?’ That’s when I knew. Hearing that, even at 11 years old, I realized I wasn’t going to see my mom for a long, long time.”

“When the bus pulled up, all the kids saw the police cars surrounding us. My mom kissed us on the cheek and waved goodbye.”

In his final moments with his mom, he recalled, “When the bus pulled up, all the kids saw the police cars surrounding us. My mom kissed us on the cheek and waved goodbye.”

Thomas’ grandmother was sentenced to two life sentences for her nonviolent drug crimes. His mother, Katina Smith, refused a plea agreement that would have reduced her sentence if she agreed to testify against her mother. She was sentenced to 20 years.

A story of growing up and reaching out for love

With Thomas’ mother, stepfather and grandmother all in prison, and his father in the military, Thomas realized he was “basically an orphan.” He said, “I was 11, so I couldn’t really work, but I still had to figure out a way to take care of my sisters. I told myself I was going to get a scholarship so I could get a degree and take care of my family. In the meantime, I had to do whatever I could. We were in rural Georgia. The good thing about rural Georgia is that you can always make some change working with your hands.”

He began waking up every morning at 6:00 to pull corn and pick peas before school. He said, “I had a choice: the drug game, or the corn game. I kept thinking: just don’t screw up a chance to get to college.”

It was during this time that Thomas began to realize he needed help. So he began meeting with a pastor who could help him process his pain. “We rely on the kindness and the couches of others to get us through the day,” he said. “I had multiple high school coaches who looked out for me. Multiple college coaches. Deacons. Pastors. Aunties. Uncles. Friends.”

“I had multiple high school coaches who looked out for me. Multiple college coaches. Deacons. Pastors. Aunties. Uncles. Friends.”

Thomas went on to mentor kids whose parents are incarcerated or who abandoned them. His message to the kids ultimately was about love. “As men, as athletes especially, we don’t like to talk about love. We talk about brotherhood and all that, but not love. But it’s the most important thing in a child’s life.”

The ascension of Tim Tebow

The Broncos’ other first-round draft choice from 2010 had quite a different story. Tim Tebow’s parents, Pamela and Robert, became Baptist missionaries in the Philippines in 1985. Within two years, when Pamela became ill and went into a coma, they found out she was pregnant. While abortion was illegal at the time in the Philippines, the doctors recommended that she terminate her pregnancy. But Pamela chose to give birth to Tim.

Demaryius Thomas, left, and Tim Tebow accept the award for best moment onstage at the ESPY Awards on Wednesday, July 11, 2012, in Los Angeles. (Photo by John Shearer/Invision/AP)

Growing up in Florida, Tebow was allowed to play public high school football, despite being homeschooled. He quickly began rising to prominence through his tough play and a growing media frenzy. He was featured in Parade magazine, became the focus of an ESPN documentary called, “Tim Tebow: The Chosen One,” and was highlighted in Sports Illustrated. In 2007, his story was told on ESPN’s Outside the Lines, which focused on his political activism for homeschooled athletes to be allowed to play public high school sports.

Masculinity and militancy

Tebow’s story of his mother refusing an abortion along with him being homeschooled, a hard-nosed football player, an open proselytizer, a political activist, and popular with the media led to a legendary rise among white evangelicals in the Southeast.

In an interview with Baptist News Global, historian Du Mez talked about the role football plays for evangelicals. “Sports, especially football, serves as a metaphor for war,” she said, adding that football is “definitely the most masculine sport for their purposes.”

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

Du Mez, author of Jesus and John Wayne, reflected on Tebow’s rise to fame: “Evangelicals have long had competing ideals of masculinity. In the 1990s, with the Promise Keepers movement, there was an emphasis on servant leadership, on a kinder, gentler patriarchy. By the end of the decade, however, many evangelicals started to see this softer side of evangelical masculinity as too soft, and we see the pendulum swing back to a more rugged, tough guy masculinity. This dovetailed with a resurgence of culture wars militancy.

“Tebow is an interesting figure because he could bridge these two somewhat conflicting ideals. He was a football star — so his masculinity was never in question. And he took all the right sides in culture war skirmishes. But he was also the clean-cut nice guy, and so he was in many ways the perfect hero for evangelicals shaped by this conflicted history.”

Celebrity culture and white supremacy

Due to Christianity Today’s The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill podcast, which focuses on the masculine and militant celebrity culture of megachurch pastor Mark Driscoll, many evangelicals are beginning to deconstruct the evangelical tendency toward celebrity culture.

While this is an important conversation to have, conservative evangelical leaders on the podcast and on other platforms seem to be unwilling to examine the deeper theological roots and the systemic structures that create and sustain celebrity culture in white evangelicalism.

Regarding Tebow, Du Mez said: “Of course, there was the simple matter of celebrity culture. Evangelicals have always loved it when one of their own makes it big, regardless of the cultural space. But as a good-looking, athletic spokesperson for their faith and their politics, Tebow was especially celebrated.”

The celebration of celebrity combined with the perceived mandate of missions as proselytizing ultimately masks the systemic structures that fuel power, oppression and white supremacy.

“The celebration of celebrity combined with the perceived mandate of missions as proselytizing ultimately masks the systemic structures that fuel power, oppression and white supremacy.”

Du Mez remembered: “When I heard (Tebow) speak at an event on Christianity and sports, I was struck by how much he framed his story as being ‘blessed’ by God, and how much he was essentially proselytizing a white savior narrative in terms of his volunteer work. What was missing was any sense of privilege or of structural injustice, either domestically or in terms of his international work. This reflects the dominant approach within white evangelicalism, and I think it is part of the reason for his popularity. He models a very individualistic conception of activism, one that pays little attention to systemic issues.”

Of course, like most white evangelicals, Tebow likely would not consider himself a white supremacist or the beneficiary of white privilege. The lack of awareness may be subconscious, but it is also why white evangelicals often resonate with some stories over others.

Du Mez has noticed this discrepancy in recent years: “I was especially struck by the disparity between how (Tebow) was adulated and how Colin Kaepernick was demonized, often by the same people.” Kaepernick is the NFL player who first knelt during the National Anthem as a statement on America not living up to its ideals of liberty and justice for all.

John 3:16 goes viral

When Tebow became the starting quarterback of the Denver Broncos in 2011, his passing abilities were severely limited. The Broncos were so committed to the running game that Tebow was credited with a win against the Kansas City Chiefs after completing just two passes. Thomas, who had spent his entire life doing what was necessary for his family to survive, had to commit himself to run blocking rather than catching passes.

Florida quarterback Tim Tebow is interviewed after the BCS Championship NCAA college football game against Oklahoma in Miami, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2009. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

But the ultimate climax of their story together happened in the 2011 AFC playoff game against the Pittsburgh Steelers. On the first play of overtime, Tebow threw the ball 17 yards in the air to Thomas, who stiff-armed Ike Taylor and outran the Steelers secondary on his way to an 80-yard touchdown to win the game. Tebow ran to the end zone to kneel in prayer, a celebration that became a national social media trend called “Tebowing.”

Thomas’ catch-and-run meant Tebow finished the game with 316 passing yards at a 31.6-yards-per-pass average. As a result, 91 million people googled “John 3:16.” And the following week, Focus on the Family paid for a commercial during the Broncos vs. Patriots playoff game showing a group of kids reciting John 3:16.

President Obama’s justice or President Trump’s justice

In July 2015, President Obama pardoned 46 nonviolent drug offenders, one of which was Katina Smith, Thomas’ mom. As a result, she was able to watch Thomas and the Denver Broncos win Super Bowl 50. When the Broncos visited the White House in 2016 for their Super Bowl championship celebration, Thomas thanked President Obama and handed him a letter.

But white evangelicals had a more retributive type of justice on their minds. They were unable to celebrate the pardoning of Katina Smith and her restored relationship with her son because they were too busy promoting and electing Donald Trump as their champion of justice, claiming he would bring back the “law and order” they thought Obama had lost.

A poster or a mirror

When white evangelicals get caught up in the story of Tim Tebow, they see a mom who promotes the pro-life movement, a homeschooler who advocates for their positions on education, a football player who confirms their values of masculinity and militancy, and a Baptist missionary who advances their agenda through proselytizing and white savior volunteer work.

But if white evangelicals were to listen to the story of Demaryius Thomas, they would have to face the questions of why a mother would believe she had to sell drugs in order to help her child afford to buy comparable clothes to his classmates, why an 11-year-old would wake up to loaded guns and then have to pull corn every day at 6 a.m. to provide for his siblings, why prosecutors would pit a daughter against her mother, why Black women would get multiple life sentences for nonviolent crimes, and why mass incarceration has gotten so out of control.

Tebow “is in many ways a poster boy for the more attractive, respectable version of evangelical culture wars,” Du Mez said.

But Thomas is in many ways a mirror that reflects back to white evangelicalism the systems of oppression it has built and profited from.

When Thomas retired from the NFL this summer, he said, “I’m just happy to say I’m done and (football) did me well. … I did my best each and every game. But it wasn’t really about me. I just wanted to go out there and do what’s best for the team.”

Perhaps one day, we will all listen to the story of Demaryius Thomas as a reminder that we’re all on the same team, that love is the most important thing in a child’s life, and then work together to further a justice of restorative love.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a freelance writer based in South Carolina. He is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG and recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com

Related articles:

She’s Tim Tebow’s mom, but she’s got her own story too

Tebow apologetics | Opinion by George Mason

Tebowing 2.0: Prayer, the NFL and religious diversity | Opinion by Andrew Daugherty