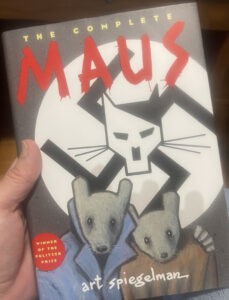

Several folks have asked my opinion about the recent controversy over the book Maus and its removal from the middle school curriculum in McMinn County, Tenn.

Two disclosures:

First, I have deep and abiding family roots in McMinn County.

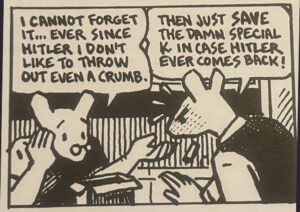

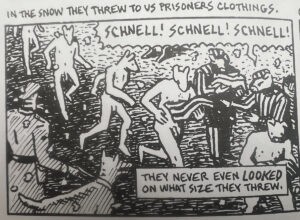

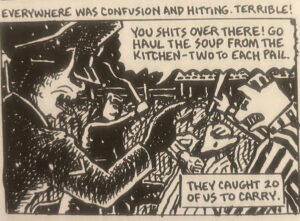

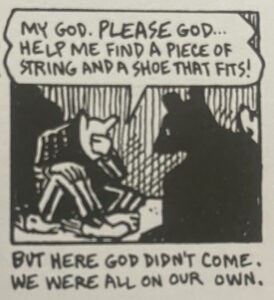

Second, I don’t hesitate to tell my closest family or friends when I think they’re wrong, and I desire and accept the same love from them. Of all the articles and social media posts I’ve seen, none has shown images or text from the book. I am including some of them here.

A theme of this response will be context, so here are a few more contextualizing observations.

I wrote my doctoral dissertation on parental mediation of children’s media engagement — specifically TV and movies, but there is much overlap with books. That doesn’t make my position correct, but I have invested much time on the topic of children and media — enough to know there are few if any easy answers.

One conclusion drawn from my dissertation research was that we cannot believe that G-rated movies are perfectly safe for kids or that R-rated movies are always unsafe.

“We cannot believe that G-rated movies are perfectly safe for kids or that R-rated movies are always unsafe.”

As a child, I had a recurring nightmare. As an adult, I saw the movie Fantasia and suddenly yelled, “That’s it!” Apparently, I had seen Fantasia as a very young child, and it scared me. Conversely, the movie The Passion of the Christ is appropriately R-rated, and showing it to children under 18 would be very subjective to the child’s tolerance. When I was a youth minister, a parent informed me that her son with autism had experienced a tremendous amount of anxiety over a video game that had been played during a youth event. We can’t lump all people into a box — much less eighth graders.

In a college ethics class, prompted by a student comment, I went to YouTube and played the euthanasia scene from Saving Private Ryan. I looked around the room and saw one young man with his head down breathing deeply. I immediately put two and two together and realized he was a veteran. I paused the film and vehemently apologized for my insensitivity. He emphatically said something like, “No! Do not apologize. This is hard, but I have to be able to cope with this kind of thing.” He then told the class that while he never had been in combat, he had found a fellow veteran who had taken his own life by gunshot. That was an adult having to wrestle painfully with the intersection of life and media used in class.

In a college ethics class, prompted by a student comment, I went to YouTube and played the euthanasia scene from Saving Private Ryan. I looked around the room and saw one young man with his head down breathing deeply. I immediately put two and two together and realized he was a veteran. I paused the film and vehemently apologized for my insensitivity. He emphatically said something like, “No! Do not apologize. This is hard, but I have to be able to cope with this kind of thing.” He then told the class that while he never had been in combat, he had found a fellow veteran who had taken his own life by gunshot. That was an adult having to wrestle painfully with the intersection of life and media used in class.

My syllabi give college students the opportunity to request an alternative assignment if something in the description feels outside their personal boundaries. I only recall one time when that has been exercised, but we talked through it, the student had solid grounds for discomfort, was aware of the need to work through that discomfort but was not at a place to do it at the time. I gladly gave an alternative assignment. (Physicians have a good rule: “First do no harm.”) Likewise, when I lived in Knoxville, Tenn., parents were sent notifications about movies to be shown to their children at school.

About the word ‘banned’

The word “banned” has been used a great deal in reference to what the McMinn County School board did. While it is technically true the book was banned from eighth grade curriculum, that summary makes a connotation that feels quite unfair. If we said Schindler’s List was not appropriate curriculum for eighth graders, we wouldn’t say the movie was “banned” in the generic sense.

There are many things I have shown my children in our home that I would never endorse for use in school. When my son was 10 and my daughter 16, I made them watch the horrific opening scene of Saving Private Ryan. I wanted my son, in particular, to know the horrors of war as opposed to the glamorized version he was seeing in the video games at the homes of friends. (These were games in which his sister had no interest. She had no trouble being revolted by war.)

“There are many things I have shown my children in our home that I would never endorse for use in school.”

We also watched the gory scene of Jane’s death in Breaking Bad. My son was crying, asking why Walt didn’t save her. We had a talk about the dangers of drugs and drug culture. I never would have done that with an eighth-grade class unless every parent was on board based on their knowledge of their child.

I learned this from a mistake I made at church. I had not been aware middle schoolers would be in attendance at the Bible study where I was doing a lesson on anger — particularly anger as an expression of toxic masculinity. I showed a movie clip with very harsh language, then one with kindness and positive management of anger. The whole point was that crudeness is inappropriate and gentleness is better, but several parents got upset that their children were exposed to the harsh language (that they likely had heard on the school bus since first grade).

While I strongly believed (and believe) the context of the lesson was not harmful, I did something without getting the parents on board, and that was imprudent — and I would have handled it differently had I known middle schoolers were in the room. (I also admit that even as I was watching I thought, “Oh no. I forgot how rough this scene is — especially to younger viewers.”)

Does Maus pose a risk to eighth graders?

Now, with those lengthy caveats on the table, the question is this: Does Maus pose risks that warrant it not being in the curriculum for eighth graders?

My answer is that very few things do not pose a risk to eighth graders. I once substitute taught 10th grade English, and I felt very uncomfortable that I was supposed to just babysit them while they watched Romeo and Juliet — the contemporary version with Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes. In fact, since I knew I might not be back for the end of the movie, I deviated from the teacher’s plan.

“My answer is that very few things do not pose a risk to eighth graders.”

Here’s what I said to the class: “I’m really surprised they’re letting you all watch this movie, because it’s really inappropriate — even dangerous — for teens to be watching this. Shakespeare’s intended audience was parents. It is a scathing critique of how utterly stupid parents can be.”

Looking around the room, I could tell I had them. They were wide-eyed and captivated. I turned up the heat: “We’re going to get the dangerous part out of the way first and watch the ending.” I played the double suicide scene. Then with the passionate indignation of a union leader calling for a strike, I said, “Did you see any blood when she stabbed herself? No! Look at this freeze frame. She looks like freaking Sleeping Beauty. But there is nothing beautiful about suicide, people. Nothing. Now, when we get back from lunch we’ll go back to the beginning and look at the stupid things the parents did that led to this. Then we’ll identify some alternatives to suicide when our parents are stupid.”

The great thing about Maus is that it vividly depicts the horrors of suicide. The question is, what impact does a picture of a woman slitting her wrist have on a tweenager who is toying with the idea of self-harm or already engaged in it? Does my child’s English teacher have the ability to help navigate the issue for my child?

“The great thing about Maus is that it vividly depicts the horrors of suicide.”

That said, the main issues I have seen raised about Maus relate to nudity and profanity.

If I were a referee and this controversy were a football game, I’d call offsetting penalties on both teams. Sometimes unsportsmanlike conduct is hitting; sometimes it’s cursing; sometimes it’s excessive celebration. The infractions I perceive fall under the category of “good intentions” on both offense and defense.

What about the nudity?

First, let’s take all the upset over nudity. Yes, it is well-intentioned to protect innocent eyes from premature sexuality. But, for heaven’s sake, we in the U.S. need to take a giant chill pill. We have such a puritanical view of the human form as to make it dirty in our effort to keep it pure.

Monterey, Mexico, is not exactly a hotbed of liberalism. Try taking a step where you cannot see a Catholic church in that city. But the city park features a nude statue of Poseidon, and let’s just say the likeness of the king of the ocean features more than a very large trident. Dancing in a spray of fountains around him are naked sea nymphs. The locals are not gasping in shock. But a similar statue — “Musica” — in Nashville, Tenn., raised cries of obscenity.

I suspect our American repression of artistic nudity creates a reactance effect. In other words, if there is a wooden wall with a sign that says, “DO NOT LOOK HERE,” people automatically want to look there. We are enchanted by the forbidden.

I suspect our American repression of artistic nudity creates a reactance effect. In other words, if there is a wooden wall with a sign that says, “DO NOT LOOK HERE,” people automatically want to look there. We are enchanted by the forbidden.

No, that doesn’t mean there should be no prohibitions, but to prohibit something, we need to show that it causes harm. Does the art in question inherently illicit unhealthy behavior? The nudity in Maus consists, in the first case, of the bare breasts of a woman who died in a bathtub and, in the second case, the barely discernable genitals of men who have been stripped by Nazis. I suspect anyone aroused to inappropriate behavior by this kind of nudity has problems so deep that seeing the book would be like blowing on an inferno: the breathing won’t put out the fire but it’s not significantly feeding the fire either. So, to those who complained about the nudity, I see this as a well-intentioned overreaction.

“To prohibit something, we need to show that it causes harm.”

What about the profanity?

However, the same applies to those claiming there is nothing to worry about regarding the profanity. I know they have the good intention of not wanting an appropriately graphic story of the Holocaust to be lost due to “some bad words.” Yes, bad guys do bad things. So, it seems like a good thing to have the Nazis saying awful things. This associates scatology (crude language) with despicable behavior.

However, most often in Maus, it is the protagonist who is using the coarse language. I recently read a Facebook post that said there was only one occurrence of profanity in the book. I haven’t been able to tell which version of the book McMinn County was addressing. Maybe it was just volume one. I read the “complete” version, and there are, in fact, several occurrences of profanity.

However, I think the ultimate issue is not the quantity but the nature of the profanity that raised concerns. And the nature of the profanity is quite different than the bad guys using bad language.

However, I think the ultimate issue is not the quantity but the nature of the profanity that raised concerns. And the nature of the profanity is quite different than the bad guys using bad language.

The most common crude word in the book is common slang for defecation. The fact that we Americans find that word to be crude while we have no equal reaction to the word “dung” raises issues beyond the scope of this essay. For now, suffice it to say that many find the word offensive and wouldn’t want their child following that example of the protagonist.

But likely the greater concern should be to the sensibilities of those who take seriously the biblical command to “honor your father and mother.” At one point the author yells an epitaph of damnation at his father. Now, the context is that the author had just discovered that his father had destroyed the author’s mother’s diaries. It is an incredibly painful scene to read. Granted, in the next frame the father says such language never should be said to anyone, much less one’s own father. But imagine an eighth grader screaming this at his or her parents and the parents finding out he or she read it in a book at school.

Thus, I take issue with those who say, “There is not much profanity in the book” without acknowledging the nature of the profanity in the author’s casual crudeness or parent-targeted rage.

There is another way

These folks typically say the issue of the Holocaust should not be overshadowed by the language. I fully concur. For that reason, the authors and publishers could have created a version with the language redacted. The author of the book is rightly held up as a literary hero for creating this brilliant Pulitzer-Prize-winning work.

I recently purchased a Kindle version of another book on the Holocaust: Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. When I opened it, I realized I had inadvertently selected the “Young Adult Version.” I then ordered the original. I have not read both to compare them, but clearly the author or editors felt that at least on the linguistic level, it was important to make the book developmentally appropriate for younger readers. Thus, those who say that the issue of the Holocaust is more important than the language actually make an argument for making a version that would keep the focus on the Holocaust.

Interestingly, one of the controversial passages of the book has neither profanity nor nudity. One of the McMinn County School Board members explicitly referenced the passage as problematic. In the book the author asks his father about his love life prior to meeting the author’s mother. The father boasts with some swagger about his premarital sex life. In a community with strong mores about premarital sex, it seems legitimate to wonder what impact will be had on an eighth grader’s view of propriety if a school textbook’s protagonist is boasting about sexual exploits.

Interestingly, one of the controversial passages of the book has neither profanity nor nudity. One of the McMinn County School Board members explicitly referenced the passage as problematic. In the book the author asks his father about his love life prior to meeting the author’s mother. The father boasts with some swagger about his premarital sex life. In a community with strong mores about premarital sex, it seems legitimate to wonder what impact will be had on an eighth grader’s view of propriety if a school textbook’s protagonist is boasting about sexual exploits.

Now, folks on the left are going to think such folks are just uptight about sex. My question to them is, how do you feel if your child’s eighth grade teacher is not addressing the inherent sexism that is depicted? One panel in the comic-style book shows a large group gathered around a dinner table. One of the men says, “Let’s play rummy while the women clear the table.” This most certainly offers a historically accurate portrayal of the time and culture. But is this complementarian behavior by one of the protagonists something folks want children to emulate? Folks on the right would say absolutely; folks on the left would say absolutely not. How is an eighth-grade English teacher going to navigate this? Are parents being given a heads up about such issues?

The difficulty of being an eighth-grade teacher

The fact that there will be so many kinds of reactions to the preceding paragraphs raises the issue of pragmatic politics in a diverse public school system with a wide variety of sensibilities.

Think of the scene in the movie Dead Poets Society where the teacher calls on a student to read aloud. Now imagine calling on an eighth grader to read aloud a passage where an adult son curses his father. As mentioned above, I think the showing of Romeo and Juliet to high school students is dangerous without proper mediation.

Are eighth grade English teachers equipped to help each student in the class deal with the words and images in Maus? I came home from a high school class quite traumatized from being required to watch Helter Skelter as a tool for examining historical criminals like Charles Manson. I was consumed with anxiety and couldn’t sleep. True, that often was the case even before I saw the movie. The movie just added a twisted religiosity about it.

Are eighth grade English teachers equipped to help each student in the class deal with the words and images in Maus? I came home from a high school class quite traumatized from being required to watch Helter Skelter as a tool for examining historical criminals like Charles Manson. I was consumed with anxiety and couldn’t sleep. True, that often was the case even before I saw the movie. The movie just added a twisted religiosity about it.

Should a teacher have to consider every student’s fragility? Are they — on an individual basis, without collaboration — broadly equipped to do so? While I and my children were blessed with many, many great teachers, we each had a small handful of teachers who — like a small percentage of employees in any profession — were ineffective.

Thus, in my view, it is patently unfair to say that those with apprehensions about this book’s universal appropriateness for eighth graders were trying to suppress discussion about the Holocaust. One school board member said he spoke to a rabbi who said he wouldn’t want the book used at his synagogue. On the other hand, it is patently unfair to assert that those opposing its removal are just “being woke.” The slaughter of millions of people is a very legitimate concern. The current war in Ukraine demonstrates the legitimate concern of how we as a global community deal with tyrants.

So, what are the solutions? First, there are no easy solutions. That’s part of the problem. School administrators don’t like headaches, and there is no world in which this book and ones like it are not going to cause a headache — either from those who want it taught or those who object to it being used.

Here’s what I would do

If I had fiat, here’s what I would do, but first an explanation of why I would do it.

Ancient Hebrews considered the biblical book of Ezekiel too racy and too complex to be tackled until the reader was at least age 30. We wouldn’t say that ancient rabbis were “banning” Ezekiel. We would say they were reserving the book for an age-appropriate audience based on their norms. Similarly, as alluded above, I think it highly unlikely that the movies Schindler’s List or Saving Private Ryan would be shown at the middle school level. I have a friend who, due to a particular nude scene, refused to sign a permission form for his 17-year-old to watch Schindler’s List in a high school history class. I thought my friend was being uptight, but the school gave parents the right to give informed consent.

As I recall, when Saving Private Ryan was aired on network television, a judge granted a waiver over FCC rules related to profanity. He or she said something like, “We shouldn’t try to clean up World War II.” However, I noticed the broadcast version of Schindler’s List left in profanity but did not contain the topless bedroom scene my friend objected to his teen seeing. There is a long history of editing and distributing material based on age-related issues.

Thus, I applaud the McMinn County School Board for being cautious with the young minds in their charge. With equal fervor I applaud those who insist that young minds need to be exposed to and taught about the disturbing issues addressed by Maus. To that end I think a version easily could be produced that keeps the focus on the Holocaust. An important aspect of this is the generational trauma that led to a son yelling obscenities at his father. But that could be done in a way that redacts the language and images just as a newspaper would.

“Regardless, a piece of literature like this requires parental involvement.”

Regardless, a piece of literature like this requires parental involvement. A colleague of mine once required high school students to watch Man of La Mancha for a Spanish class at a private Christian academy. Some of the parents were angry about their children viewing Sophia Lauren’s lowcut top and cleavage. I helped my colleague write a family discussion guide, and feelings were assuaged when it was pointed out that, first, Dulcinea transforms from sad and promiscuous to wholesome and joyful, and, second, that the images were no worse than walking down the street, and we need to be prepared for that.

Applying that to Maus, a diverse group of parents could create a list of controversial issues and images in this great work and allow parents to address these issues at home in keeping with their values. Parents who completely object could have their children given an alternative assignment. Would this be awkward for some? Certainly. Just as it was awkward for my friend who was a Jehovah’s Witness who did not pledge the flag or participate in birthday parties.

E-Pluribus Unum is messy. That mess must not be addressed with the easy answers of either “everything goes” on the left hand or “throwing out the baby with the bathwater” on the right hand.

Brad Bull holds a master of divinity in pastoral counseling and a Ph.D. in human ecology. He is a licensed marriage and family therapist in private practice and has served many years as a college professor. He is very glad that, in sixth grade, since he had an 8 p.m. bedtime and could not watch Roots on TV, he read the book from his school library. But he resents being made to watch Helter Skelter in a high school classroom with no sensitivity to its potential impacts. He is grateful to friends and colleagues across the theo-political and educational spectrums who provided feedback on this essay.

Related articles:

The Maus saga: A case study of our present crises | Opinion by Bill Leonard

It was fundamentalists who taught me about soul competency, and now they want to ban books? | Opinion by Susan Shaw

That time I went to the school board meeting to speak against banning books | Opinion by Mark Wingfield