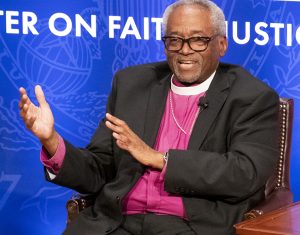

Don’t be fooled by the “Christian” in Christian nationalism, warns Michael Curry, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church.

“What we’re actually describing is an ideology that’s not really a religion, but it looks like a religion and uses and invokes language and symbols that have religious trappings. … I think some innocent people are being fooled by it,” Curry said during a panel discussion on white Christian nationalism hosted by the Georgetown University Center on Faith and Justice and moderated by its director, Jim Wallis.

The term “Christian nationalism” has become so pervasive that it could be misunderstood, he warned.

Curry was joined on the panel by Amanda Tyler, executive director of Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and lead organizer of Christians Against Christian Nationalism, and Samuel Perry, a University of Oklahoma sociologist and co-author of The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy.

The Oct. 26 conversation began with a question on how to define “Christian nationalism” given the term’s increased use amid the rise of American cultural and political tensions. Curry expressed concern that citizens in the political and religious middle may confuse the ideological movement with faith itself.

“Christianity is about the way of Jesus of Nazareth, it is about the way of living love in our lives. Anything that’s not that, is not Christianity.”

“Part of our task is to help normal people, the sensible center, to be clear that Christianity is about the way of Jesus of Nazareth, it is about the way of living love in our lives. Anything that’s not that, is not Christianity.”

Perry said Christian nationalism is an ideology that glorifies and champions a blending of U.S. civic life with a very specific brand of Christianity.

Samuel Perry

“That is a Christianity that isn’t characterized by giving my life to Jesus or wanting to be a good disciple, but it is about a white Christian ethno-culture,” he said. “For white Americans, it seems to connect with this idea of nostalgia for an earlier time when the right people were in charge and when the right cultural values held sway.”

Christian nationalism also is a political strategy often used by leaders who are not necessarily Christian nationalists themselves, Perry said. “A good example of this is (Donald) Trump. … I think it’s fair to say that Trump probably doesn’t believe much of anything other than winning, and he believes in his own influence. And yet he is more than willing to leverage white Christian nationalist rhetoric to be able to mobilize those audiences.”

Perry said recent research has found a decline in the percentage of Americans who believe the federal government should declare the U.S. a Christian nation, which is one of the tenets of Christian nationalism. But that decline since 2017, from 30% to 20%, comes as the ideology is being increasingly adopted by the Republican Party and politicians “trying to appeal to a reactionary white Christian base who is very anxious and very angry.”

That makes the ideology very dangerous to democracy and faith, Tyler said. “It’s the single biggest threat to religious freedom because Christian nationalism, as a political ideology and a cultural framework, creates second-class citizens for everyone who’s not Christian in their view.”

Amanda Tyler

But the allure of Christian nationalism runs deep because its goal of establishing a white, Christian nation has existed since the founding of the United States with the blessing of institutions of faith, she said. “Based on how complicit the church was in slavery, in segregation, in lynchings, in all of those things, we have to acknowledge that American Christianity has been compromised by Christian nationalism for centuries.”

Christians against Christian Nationalism was in part founded to inspire Christians and congregations to examine their beliefs and practices for elements of this heresy, Tyler said. “If we don’t get right with our own theologies and our own practices first, we won’t be able to be the kind of witness we need to the rest of the world to dismantle Christian nationalism.”

“When you take those arguments and lay them alongside Jesus of Nazareth … you will see a wide gap that cannot be closed.”

Being that witness begins with comparing the messaging of Christian nationalism with that of the four Gospels, Curry said. “Let us not forget that chattel slavery in America was justified by pro-slavery, Christian-sounding voices. When you take those arguments and lay them alongside Jesus of Nazareth … you will see a wide gap that cannot be closed. The same is true if you look at the complex of white Christian nationalism as an ideology — you lay it alongside Jesus of Nazareth and we’re not even talking about the same thing.”

Michael Curry

Curry also called for “ecumenical, interfaith, bipartisan, multiracial, multicultural, multireligious” coalitions to push back against Christian nationalism with a compassionate counter-narrative.

“There does have to be the kind of education that … there actually is a way of being Christian that is not exclusive, that you may vote your way and I may vote my way based on our values and our own discernment.”

The worst thing Americans can do is nothing to oppose Christian nationalism, he added. “Silence is complicity, and silence creates a context in which something like that can grow, and when something like that can grow … it just starts spreading … so you’ve got to confront and name it.”

Related articles:

Once again, white evangelicals are outliers on beliefs about race and American history