Lurking in the carnage of the cultural un-civil war, there lies the determined opposition of many Christians to the Social Gospel.

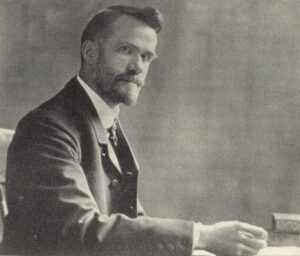

Two powerful movements in the 20th century, one theological and one political, produced a furious opposition to the Social Gospel. The theological movement centers around Walter Rauschenbusch. The political movement revolves around Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Rauschenbusch, a Baptist seminary professor, and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a rich New York politician, haunt evangelical Christians still.

Rauschenbusch taught that the purpose of Christianity was to transform human society in accordance with the will of God. Christians are supposed to influence the systems that create evil in the world. He identified the economic exploitation of the poor as a national sin.

“Rauschenbusch taught that the purpose of Christianity was to transform human society in accordance with the will of God.”

He wrote his classic book, Christianity and the Social Crisis, as a pastoral response to his congregation comprised of the working people on the West Side of New York City. He said, “I feel I owe help to the plain people who were my friends.”

Philosopher Richard Rorty, no friend of Christian faith, wrote: “Rauschenbusch hoped to persuade (us) that it was society, rather than individual souls, that stood in need of redemption – that (we) should not think of Jesus as personal savior.”

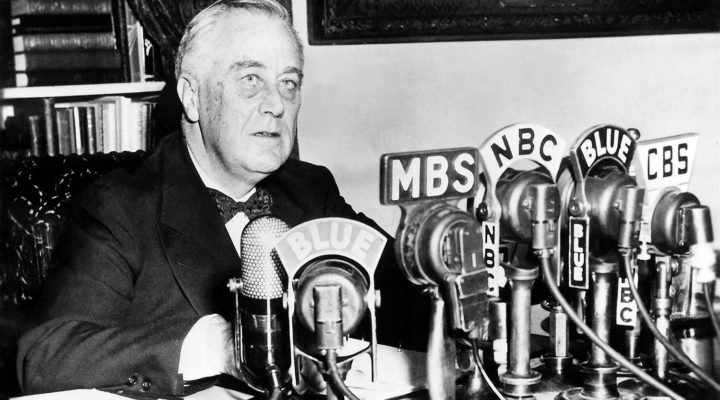

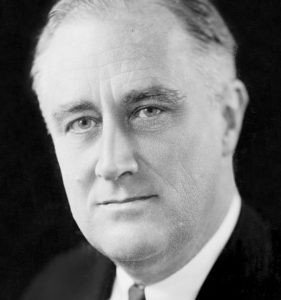

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Roosevelt is the political enactment of the Social Gospel of Walter Rauschenbusch. He donned the clerical robes of the civil religion’s chief priest, primary prophet and senior pastor. Mary Stuckey puts it best: “Roosevelt assigned to himself the protection and guidance of the nation’s spiritual health. He supervised the rhetorical creation of the nation as a spiritual neighborhood.”

From Reagan to Trump, the modern Republican Party has sought increasingly to undo Roosevelt’s legacy, which was inspired by Rauschenbusch’s theology. No president has made the undoing of Roosevelt’s legacy the focal point of his administration like Donald Trump. For Roosevelt, America was about the potential to be the “good neighbor” to the world; Trump wants to build walls of separation and preaches isolationism centered in “America First.” Although Trump has no theological basis for his politics, many of his followers believe they are doing God’s will by following Trump.

When Robert Jeffress admitted on national television that he wanted the meanest son of a bitch he could find as his president, he was speaking of Trump. This startling statement from an evangelical pastor reminded me of a testimony from a working man during Roosevelt’s first term as president: “Mr. Roosevelt is the only man we ever had in the White House who understands that my boss is a son of a bitch.”

Rauschenbusch, even after 100 years, still is accused by evangelicals of not understanding the person and work of Jesus. This seems a strange accusation from people who have abandoned Jesus outside of the constant use of his “name.”

“Rauschenbusch, even after 100 years, still is accused by evangelicals of not understanding the person and work of Jesus.”

Evangelicals also insist that Rauschenbusch didn’t understand the radical nature of sin. The social and systemic nature of sin, the overwhelming evil within the systems of human arrogance, speak of far greater sin than the peccadillos of evangelical preachers. They rail against “sin,” but Rauschenbusch dared preach against “Sin” — the flaws of America, the manifold wickedness of a system rigged against the poor.

Walter Rauschenbusch

And of course, Rauschenbusch, according to his critics, doesn’t offer personal, individual salvation. Evangelicals insist Rauschenbusch had a low view of the church. This accusation falls flat when considering that evangelicals have turned the church into a political arm of the Republican Party, having planted the American flag where the Cross rightly belongs.

The Social Gospel and the “New Deal” disrupt the conservative evangelical world.

Franklin Graham has unleashed a recent attack on progressive Christianity that underscores the unending animosity evangelicals feel toward the Social Gospel. Graham insists that “progressive Christianity is not a gospel at all.” He makes a clear distinction between progressive Christianity and his version: “When the topic of justice is discussed, progressive Christianity is primarily concerned with the issues of social and racial justice (which the Bible does address), but most often neglects the far more fundamental issue of God’s justice — how a holy and just God deals with sinful and wicked men.”

Never given to reticence, Graham insists “progressive Christianity can send a person to hell.”

Roosevelt made the Social Gospel part of the federal government. He attacked the social evils of his day with legislation that provided help on a national scale. Stuckey argues, that “the rhetoric of the ‘good neighbor’ operated as an overarching governing philosophy of the Roosevelt administration. In his first inaugural address, Roosevelt said, ‘In the field of world policy I would dedicate the nation to the policy of the good neighbor — the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others — the neighbor who respects his obligations and respects the sanctity of his agreements in and with a world of neighbors.’”

“Roosevelt made the Social Gospel part of the federal government.”

Roosevelt said: “Friendship among nations, as among individuals, calls for constructive efforts to muster the forces of humanity in order that an atmosphere of close understanding and cooperation may be cultivated. It involves mutual obligations and responsibilities, for it is only by sympathetic respect for the rights of others and a scrupulous fulfillment of the corresponding obligations of each member of the community that a true fraternity may be maintained.”

For Roosevelt, friendship was crucial. Words like “cooperation” and “understanding” and “compassion” mattered. Roosevelt promoted mutuality, trust, fulfillment of obligations and confidence. American historian Robert McElvaine says these are the same qualities in the hearts of most Americans that enabled our nation to survive the Great Depression.

Ministry volunteers serve food pantry clients at Rauschenbush Metro Ministries.

Stuckey summarizes: “For FDR, true democratic politics involved ‘a spirit of justice, a spirit of teamwork, a spirit of sacrifice, and, above all, a spirit of neighborliness.’ Neighbors worked hard to be fair to one another, to support one another, and to give what was required for the common good.”

The Good Neighbor Policy concentrated on shared core values with the American people. Roosevelt spoke with a rhetoric of shared hardship, sacrifice and interdependence. He presented Congress with a range of communicative practices in the service of high-quality political discourse and governmental policy. Roosevelt invited the people into a commitment to shared values and practices. He worked to create a more equal playing field for all Americans.

Evangelicals have led the opposition to national health insurance, to the nation’s response to COVID, to environmental issues including climate change. These oppositions originated in the conservative opposition to the Social Gospel.

“Rauschenbusch’s Social Gospel and Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy are a matched pair.”

In direct contrast, Rauschenbusch’s Social Gospel and Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy are a matched pair. As George Lakoff puts it, “The ethics of care shapes government.”

A caring government expresses empathy for the plight of its citizens, takes responsibility for the systemic issues that hurt citizens, and acts powerfully and courageously to help. Roosevelt insisted the government’s tasks were to protect and empower. Protection means far more than a strong military, more than police forces, and more than security from terrorism. Protection includes social security, disease control and public health, safe food, disaster relief, health care, consumer and worker protection, environmental protection.

A defeat for the Social Gospel is a defeat for democracy. A government of the people, for the people, and by the people needs a Social Gospel. Roosevelt saw this with clear 20/20 vision. He seemed determined to enact the “politics of Jesus” found in Luke 4: “The Lord has anointed me” — a theological vision — and “to preach good news to the poor” — an economic vision — and “to recover the sight of the blind” — an educational vision — and “to let the oppressed go free” — a vision of liberation.

If we are preaching a gospel that has no social component, no politics of care, no economic hope for the poor, no empathy for the common good, it’s no gospel at all. The gospel is social or it’s not gospel.

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor in New York state and serves as a preaching instructor at Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

The true gospel is social | Opinion by Robert Sellers

Pastor seeks Southern Baptist resolution denouncing social justice

SBC leaders criticize Glenn Beck’s choice of words, but say he has a point

Raushenbush named leader of Interfaith Alliance

Do Franklin Graham’s accusations against progressive Christianity hold up against truth? | Analysis by Patrick Wilson

FDR: When an appeal to Scripture united a divided nation