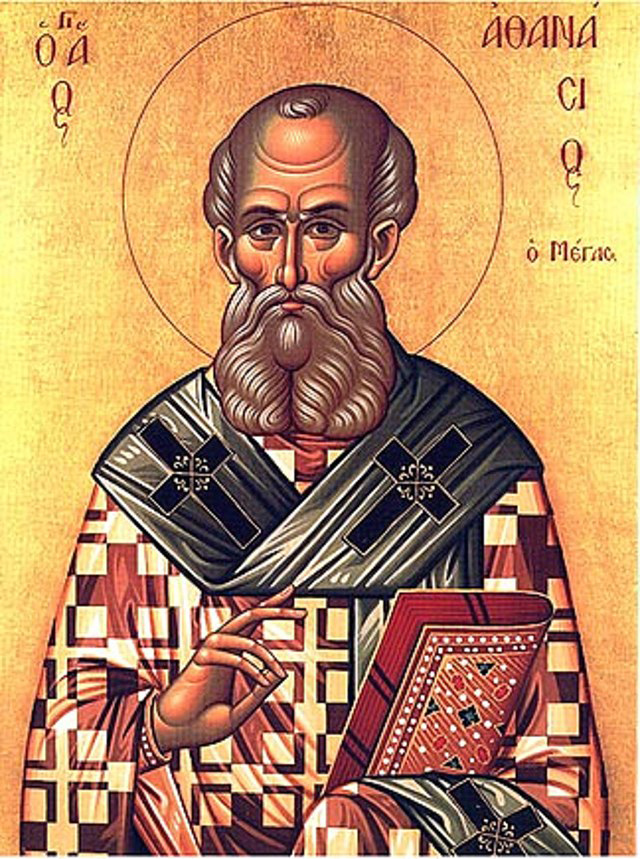

What is the Bible?

Christians may think of the Bible as the “word of God,” a guidebook for life, a book of stories or sayings that teach spiritual lessons about what it means to be a human. As kids, we may have thought of it as those hard-covered books sitting on the backs of church pews. You know, that thing the preacher carries around, and sometimes reads from.

If you grew up like most Christians in the American South, you probably learned about biblical inerrancy, the notion that everything written in the Bible is literally true. There are no faults or issues with the Scriptures, and any perceived conflicts or errors cannot be changed and should not be questioned.

Fragment of Septuagint

So, you probably never thought to ask, or never thought you were allowed to ask: How did the Bible come to be? Of course, there must have been humans remembering the stories and writing them down, and at some point in time, someone had to place them all together in an orderly fashion. How did that happen?

I never asked this question growing up in church, and it wasn’t until I reached college that I learned how the Bible’s books were written, preserved, chosen and canonized. The word “canon” is used to describe the agreed-upon set of writings that make up what we know today as the Bible. “Apocrypha” books are those of disputed authority that are not included in a faith tradition’s official canon.

This past holiday season, I realized this part of church history is something the church probably should talk about more often. Prompted by a conversation about an article I’d written on a character from one of the apocryphal texts — and about what other texts are out there aside from the stories we read in church — my aunt Janice made an observation: It makes you wonder, who had the authority to choose what was in the Bible? We put a lot of trust in other people to tell us this information, but there is so much more out there that pastors don’t even mention in church.

I have been thinking about this question since then, and she’s right. There was a point in time when the church fathers chose what was, and what was not, in the Bible. And Christians do not often talk about the texts that got cut from the final draft.

So, here goes: A brief history of how the Bible came to be.

Oral tradition

It is often assumed by scholars that oral tradition among early Israelite communities is where the contents of the Bible originated. This, of course, cannot be proved with documented manuscripts, so it is difficult to point to a specific date or year when the stories found in the Hebrew Bible, what Christians call the “Old Testament,” began to exist.

Original Manuscripts: Hebrew Bible

There has been debate about when the Hebrew Bible began to be written down, but the oldest possible manuscripts of a biblical text archaeologists have found are the Ketef Hinnom Scrolls, which were written in the seventh century BCE. They read in Hebrew, “May Yahweh bless you and keep you; May Yahweh cause his face to Shine upon you and grant you Peace.” This is similar to Numbers 6:24-26.

Entrance to Qumran Cave 11 (Photo courtesy of:

Alexander Schick)

It is possible that Hebrew literature existed in some form well before 700 BCE, but we do not have those physical documents. The earliest copies of parts of the Hebrew Bible are from the Dead Sea Scrolls, a set of texts found in the Qumran caves and that include both biblical and non-biblical manuscripts. These can be dated between the third and first centuries BCE.

The Masoretic Text, produced in the 10th century CE, was the first complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. This text is still used in synagogues today and is the complete Hebrew manuscript on which all modern English translations of the Old Testament are based.

The first ever known Bible translation is the Septuagint, the first Greek translation of Hebrew Scriptures. The Septuagint was created for Greek-speaking Jews and included books Jews eventually decided weren’t authoritative. But Christians at the time accepted these books as having some kind of authority, even though eventually Christians would come to disagree about this. These texts are the Apocrypha, scripture for Catholics and Orthodox, not for Protestants.

Original manuscripts: Greek New Testament

The New Testament texts are easier to trace since these letters and narratives were better preserved by early Christians. Although there are debates on the exact dating of each New Testament book, it is agreed that all the books found in the canonized New Testament were written between 48 and 125 CE.

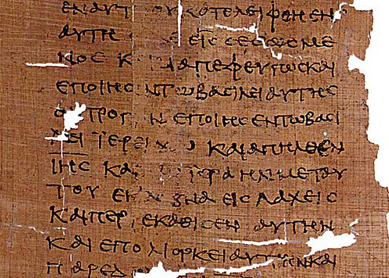

Codex Sinaiticus

The first unified collection of New Testament books came about in the late fourth century CE: the Codex Sinaiticus. Curators of a preservation project describe the Codex Sinaiticus as “one of the most important books in the world. Handwritten well over 1,600 years ago, the manuscript contains the Christian Bible in Greek, including the oldest complete copy of the New Testament. Its heavily corrected text is of outstanding importance for the history of the Bible and the manuscript — the oldest substantial book to survive Antiquity — is of supreme importance for the history of the book.”

The Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter

It was not until the late fourth century that the collection of books in the New Testament were first recognized as “canonical” alongside the Hebrew Bible.

Icon of St. Athanasius

In 367 CE, the church father Athanasius wrote his Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter, in which he acknowledged what is called the “closed canon” of the Bible. Although disputed by others, his letter ultimately mirrored what would become canonical in the New Testament, drawing a sharp line between the texts he saw fit for ecclesiastical use, and those texts he thought were heretical and therefore considered “Apocrypha.”

This letter was a response to the battles against heresy early church fathers were experiencing at the time. Athanasius wanted to protect Christian orthodoxy from Arianism, the non-trinitarian heresy that Jesus was not God, but a creature made by God, and thus subordinate to God the Father.

At this point in time, Athanasius provided an important basis for the biblical canon, although conversations on what books should be considered “canonical” continued for quite some time. It was not until April 1546 during the Council of Trent that the Latin Vulgate translation was affirmed as the authoritative version of Scripture.

And thus, the Bible as we know it was born.

Translation history

St. Jerome icon

The Latin Vulgate was translated by St. Jerome in 382 CE. This was the first complete Latin version of the entire Old and New Testaments plus the Apocrypha, translated for use in the Latin-speaking church at the time. Although there were other Latin versions of the Bible before this, the Vulgate standardized them. Additionally, different versions of the Vulgate have existed throughout church history, such as the Gutenberg Bible published in the 1450s but not used by many Christians today.

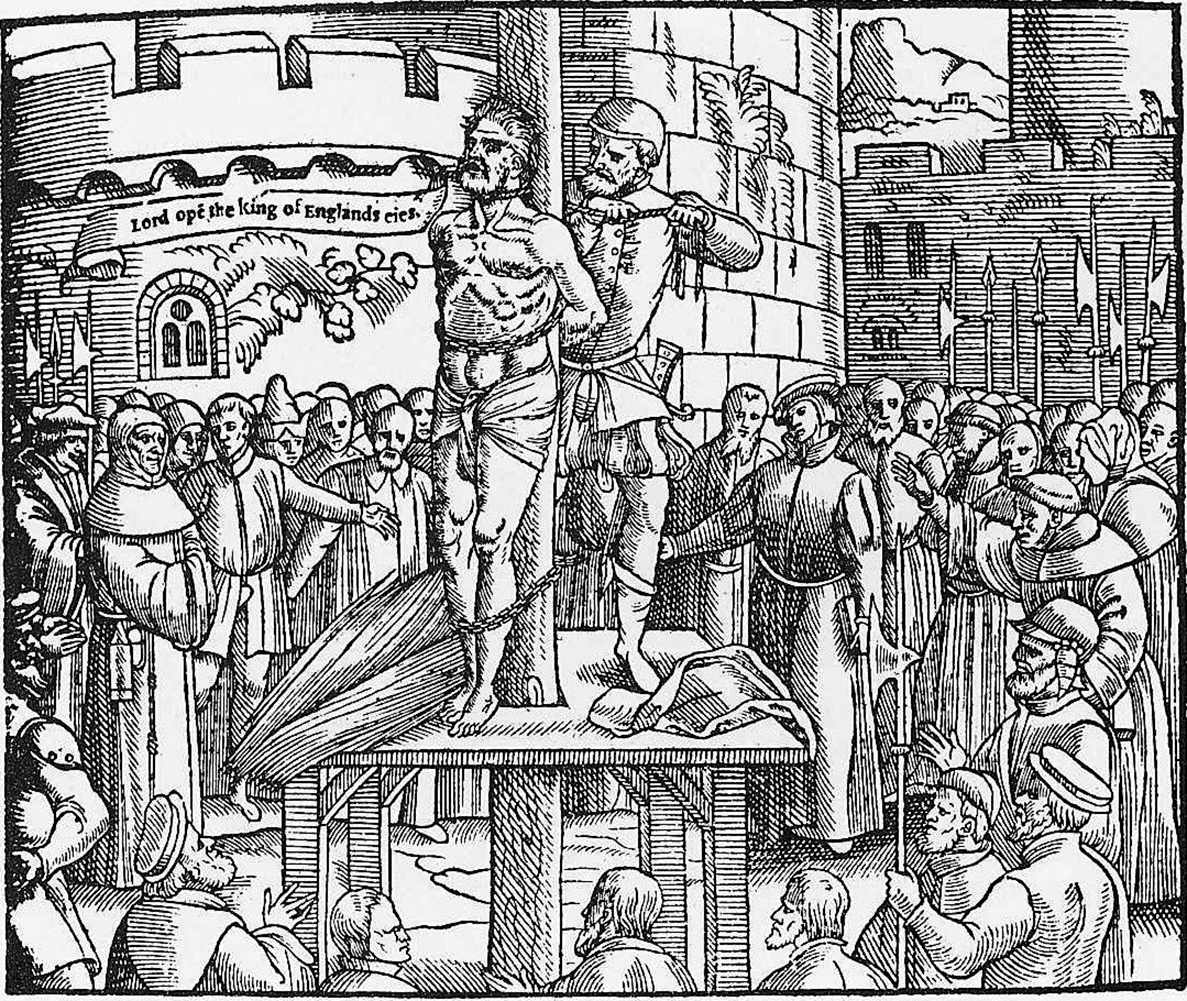

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs shows Tyndale being throttled and burned in Antwerp.

William Tyndale’s New Testament became the first printed part of the Protestant Bible translated directly from Hebrew and Greek.

At the time, it was illegal to translate the Bible into a vernacular language, although Tyndale did so anyway to make the Bible more accessible for reading. Because of this, he was executed by the Catholic Church in 1536, prior to the completion of his Bible translation. Miles Coverdale completed the translation for him, finishing the first ever complete translation of the Bible in English.

Later, the Douai-Rheims Bible was translated, not from the original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts, but from the Latin Vulgate into English, published in two different parts. The New Testament was published in 1582, and the Old Testament was published 30 years later between 1609-1610. The Douai-Rheims Bible was the standard Bible for English-speaking Catholics until the 1960s, and because it is intended for use in the Catholic Church, it includes some texts that do not appear in Protestant Bibles.

These historical Bible translations set the stage for modern translations that are recognizable to Christians today. Now, all modern English translations of the Bible are based on the Hebrew and Greek texts, not translated through Latin. Thus, from oral tradition through Hebrew, Greek, Latin and English, the collection of books we now call the “Bible” has quite a long history.

Mallory Challis

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

How to pick a Bible that’s right for you | Analysis by Mallory Challis

After 30 years, the NRSV gets an update: Here’s what that means

Many powerful women have been airbrushed out of biblical history, but this one is especially curious | Analysis by Mallory Challis