Judge Thomas Wingate, circuit judge for the 48th judicial district in Franklin County, Ky., has dismissed a lawsuit filed by writer and Kentucky farmer Wendell Berry and his wife, Tanya. Their suit sought to stop the University of Kentucky from removing a mural that has been the object of protests for its depictions of Black people and Native Americans.

But the ruling also protects the artwork. The mural was commissioned in the 1930s and was painted by Ann Rice O’Hanlon, a relative of Tanya Amyx Berry.

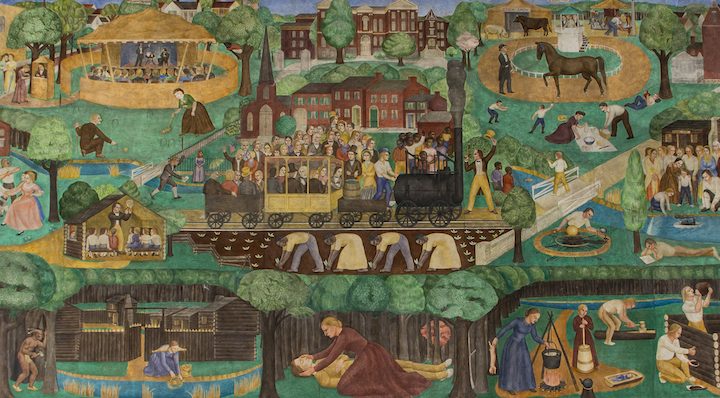

The wall-length mural is covered with vignettes intended to illustrate Kentucky’s history. At the center is an image of enslaved people tending to tobacco plants and at the bottom, there is a Native American man holding a tomahawk and peering out from behind a tree at a white woman as if poised for attack.

Judge Wingate acknowledged the historical significance of the artwork and stated that removing it would be an “insult” to Kentucky residents. He reasoned the mural did not glorify slavery or the taking of Native American territory; rather, it succinctly depicted Kentucky’s history from 1792 through the 1920s.

“The ruling seems convoluted but what is clear here is the invasion of the culture war.”

The ruling seems convoluted but what is clear here is the invasion of the culture war. And somehow, the Baptist farmer and poet has entered the fray.

The mural controversy illustrates how our culture has been imprisoned in a dualism — an “us” vs. “them” demagoguery. Patricia Roberts-Miller helps me stay centered when she reminds us demagoguery correlates with authoritarianism as a kind of propaganda that enflames a pre-existing culture of fear, anger and hatred, relying on “us” vs. “them” perceptions.

This “us” vs. “them” scale is an inaccurate metaphor. George Lakoff says the brain has both conservative modes of thought and progressive modes of thought. When a conservative offers progressive thought in public, chances are she or he will be censored by fellow conservatives. If a progressive suggests conservative thoughts, she or he will be criticized and mistrusted by fellow progressives.

Wendell Berry

Although hard to understand, I have decided to give Berry the benefit of the doubt because he has been right so often.

Over the decades, he has opposed the Vietnam War, nuclear weapons, the death penalty and coal production. He has supported same-sex marriage. I am a member of his fraternity.

But his defense of this mural gives me pause.

The attempted removal of the mural for being “racially offensive” feels like traversing an open field of land mines. An entire regiment of cultural war issues has entered the fray: the meaning and purpose of history, Critical Race Theory, freedom of speech, political correctness, wokeness, cancel culture, racism, shame and reconciliation. All these issues may be subsumed within the overriding subjects of history and race.

History

Telling the story of slavery, lynching and segregation has sharp edges and evokes deep emotional responses. From a historical perspective, there’s a qualitative difference between Lost Cause white supremacists protesting the removal of a Confederate general’s statue and African American students being offended by a mural depicting slaves. Confederate generals were traitors to the United States of America.

“God knows the difference between the groaning of slaves and the whining of the privileged.”

The problem is whites lack the authentic voice that cries out down the corridors of history — the voices of the oppressed, the abused, the lynched, the enslaved, the denied, the voices of those African Americans who fought and labored so long for basic civil and human rights. These fake voices never have endured the dehumanization so characteristic of so many millions of people of color. The white voices, instead of the authentic cry — the groaning that draws the ears of God — sounds like mere inarticulate whining. God knows the difference between the groaning of slaves and the whining of the privileged.

Moving the mural doesn’t cancel history. Our concern here is with the students of color and not a 1934 mural. This is not a disrespect of history. Nor is it an attempt to rewrite history to tell a different story.

Detail of Ann Rice O’Hanlon’s mural in the University of Kentucky’s Memorial Hall.

More importantly, this is an issue of interpretation. Historian Lynn Hunt, in History: Why It Matters, observes, “Everywhere you turn, history is at issue. Politicians lie about historical facts, groups clash over the fate of historical monuments, officials closely monitor the content of history textbooks, and truth commissions proliferate across the globe. …. It is also a time of deep anxiety about historical truth. If it is so easy to lie about history, if people disagree so much about what monuments or history textbooks should convey, and if commissions are needed to dig up the truth about the past, then how can any kind of certainty about history be established? …. What is the purpose of studying history?

History as interpretation

Facts and interpretations are the heart of historical writing. Learning to love interpretation is the heart of telling our story — his story and her story. Stanley Fish (Is There a Text in This Class), via Stanley Hauerwas, taught me how to stop worrying and learn to love interpretation.

O’Hanlon’s mural is understood differently now than when she first created the artwork. She is now only one interpreter among others of her work. There simply is not “real meaning” of the mural once we understand this is no longer her work alone, but the work of everyone who observes her mural. The artwork now exists in a continuing web of interpretative practices. These interpretative strategies are at work in shaping our understanding and our conception of the meaning of the mural.

“The mural now exists as part of an interpretative community of which the artist is but a member.”

The mural now exists as part of an interpretative community of which the artist is but a member. This is not an easy community in which to dwell because, from beginning to end, it is an exercise in politics — a hashing out of the values by which the community will live.

At the heart of the mural battle, one public group of interpreters are African American students at the University of Kentucky. Their interpretation gives a different historical perspective than a 1934 white America unaware of racism and segregation.

The president of the University of Kentucky, Eli Capilouto, says, “One African American student recently told me that each time he walks into class at Memorial Hall he looks at the Black men and women toiling in tobacco fields and receives the terrible reminder that his ancestors were enslaved, subjugated by his fellow humans.”

Race

Of course, the issue of race permeates the mural battle. Here we discover another false parallel. African American students offended by depictions of slavery have nothing in common with white students getting their feelings hurt over learning about slavery in school. White people are the oppressors in American history; African Americans are the oppressed.

Ibram X. Kendi, in How to Be an Antiracist, defines racism as “a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities.” Kendi argues that “racial inequity is when two or more racial groups are not standing on approximately equal footing” and that a racist policy amounts to “any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups.”

“We will continue to struggle with the issue of race until we give more voice to African Americans.”

I am convinced we will continue to struggle with the issue of race until we give more voice to African Americans, allowing them and their families and communities to speak to us. For instance, how do African Americans thrive in a culture still enthralled with what Richard Wright called “the ethics of living Jim Crow?”

Well, keep reading. Of all the books available on race, one of the best is James Cone’s The Cross and The Lynching Tree. Cone says: “If white Americans could look at the terror they inflicted on their own Black population — slavery, segregation and lynching — then they might be able to understand what is coming at them from others. Black people know something about terror because we have been dealing with legal and extralegal white terror for several centuries.”

Or pick up Cornell West’s Democracy Matters to learn the powerful forces that work against democracy and anti-racism. West says, “The rise of an ugly imperialism has been aided by an unholy alliance of the plutocratic elites and the Christian Right, and also by a massive disaffection of so many voters who see too little difference between two corrupted parties, with Blacks being taken for granted by the Democrats, and with the deep disaffection of youth.”

Then spend some time with Eddie Glaude Jr.’s Democracy in Black with his depiction of how race still enslaves the American soul. And thrill to his hopeful analysis: “There are those among us willing to turn their backs on democracy to safeguard their privilege. We won’t allow it. No more sweet-talking. No more dancing. No one can be comfortable. And no individual or organization can say they alone represent Black people. ‘We are the leaders we’ve been looking for.’ Together, we must close the value gap and uproot racial habits by doing democracy, once again, in black. If we fail this time — and if there is a God I pray that we don’t — this grand experiment in democracy will be no more.”

I am convinced those African American students at the University of Kentucky are the leading edge of a new movement of doing democracy in full and living color for the mutual good of all people.

Where to land?

My sense of empathy comes to rest in this place of respect for the feelings of the African American students at the University of Kentucky. Regardless of how the legal battle plays out, we owe it to these young men and women to help them create an anti-racist culture. George Lakoff reminds us, “Behind every progressive policy lies a single moral value: empathy, together with the responsibility and strength to act on that empathy.”

We have some decisions to make. Are we willing to take steps to eradicate the stink of slavery, segregation, lynching, the KKK and white supremacy? Do we possess the necessary empathy, patience and courage for the ongoing repentance for our participation in the structural racism that haunts our land?

I make a modest proposal, based on Hebrew Scripture, of allowing the story of Israel to be the guide for how a people receive their history. Like the African American church choosing the Exodus as the master metaphor of their experience, I am convinced we can learn much from how the Bible tells over and over the story of Israel in all its glory and shame.

“We can be done with outmoded depictions of Blacks and Native Americans.”

From the moment of Israel being raised from slavery in Egypt to the prophet Micah, Israel is reminded in Exodus 13:14: “When in the future your child asks you, ‘What does this mean?’ you shall answer, ‘By strength of hand the Lord brought us out of Egypt, from the house of slavery” And in Exodus 20:2–3: “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery; you shall have no other gods before me.” And Deuteronomy 5:6 “‘I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.”

At home at last in the Promised Land, Joshua reminded the Jews: “For it is the Lord our God who brought us and our ancestors up from the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery, and who did those great signs in our sight. He protected us along all the way that we went and among all the peoples through whom we passed.”

Micah is the last person in the Old Testament to remind Israel: “For I brought you up from the land of Egypt and redeemed you from the house of slavery, and I sent before you Moses, Aaron, and Miriam.”

“Remember” stands as a powerful word for the people of God — Jewish and Christian. “This do in remembrance of me.” Remembrance of how Jesus died on a cross. There’s no hiding, denying or evading the suffering.

We can be done with outmoded depictions of Blacks and Native Americans. We have the capacity for empathy to identify the offense in the mural. Stereotypes of African Americans and Native Americans are not good history. Instead, such depictions are propaganda.

Culture war issues are not where most of our energy needs to go. Will moving the mural help with the healing? If the answer is only partially “yes,” then move the mural.

Our work is constantly paying attention to our history, reinterpreting the past, updating the story and reinventing a diverse, democratic and caring community, aided by memory, empathy and clarity.

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor and writer in New York state. He is the author of 10 books, including his latest, Good and Evil in the Garden of Democracy.