It’s a common scenario in church mission work: A congregation goes into an area and provides a much-needed ministry, and then they leave for whatever reason and never see the results that follow. But every now and then a chain of events will reconnect the dots and provide a peek at the fruits of their labors.

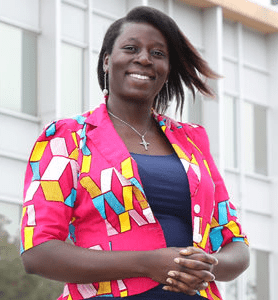

Ruth, photographed 15 years ago with Wilshire volunteer Jason Woodbury, now is married and enrolled in an apprenticeship.

For Jason Coker, national director of Together for Hope, the rural development coalition of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, that rare peek came when he noticed on Facebook that Belinda Onyango, a social worker he had known in Kenya years earlier, had a birthday. He reached out to wish her well and also to find out what had become of the child development center they had worked together to start 15 years earlier.

“I just asked her, ‘Hey, I haven’t heard anything in years. How’s everything going?’ She sent me pictures of some of the kids that started in that program,” he said. “A lot of them are in college; others have graduated and are in the workforce. The pictures of them as adults compared to them as children just blew my mind.”

A model child development center

Jason Coker

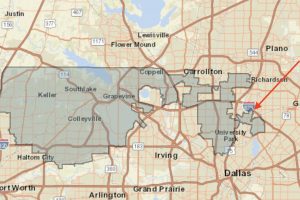

Fifteen years ago, Coker was missions minister at Wilshire Baptist Church in Dallas, and Onyango was working at a new child development center that Buckner International was starting in Busia, Kenya — located on the far western edge of the country near the border with Uganda. Many children in the town had been left parentless by HIV/AIDS, and rather than putting them in orphanages, the CDC supported them in foster care with extended family members.

Wilshire was one of a few churches that committed to helping with that effort. Over the course of three years, the Dallas church sent volunteers to Kenya several times a year, with a few church members making repeated trips and connecting deeply with the children. Wilshire gave budget funds, and individual members gave additional funds, to build the CDC, a medical clinic and a kitchen and water well.

“I was flying from Dallas to Kenya every couple of months, and we got to know the kids there and saw how they adjusted to the foster care program,” Coker recalled. “These kids were traumatized from growing up and losing their parents.”

In a recent Zoom visit, Onyango shared what has happened in Busia and in her own life.

When Coker and the group from Wilshire arrived in Busia in 2006, Onyango was employed by Buckner as a mentor at the new child development center. There were 28 children in the program starting out, and the goal of the CDC was to keep the children in family settings.

Belinda Onyango (Photo courtesy of Baylor University)

“We called it ‘kinship care’ because these kids were being supported by Buckner while living with their kin, and kin could mean probably a grandmother, uncles or aunts, or an older sibling,” Onyango explained. “And just to be clear, the kids neither had fathers or mothers. They were complete orphans.”

The CDC provided help with fees for school, supplemented their farm produce with hard-to-get provisions like sugar and cooking oil, and supplied other things needed for daily nutrition.

“Some of the children were actually born with HIV and AIDS, so we took that up also to make sure that they could access to medical facilities and medication whether they were born with HIV or not,” she said.

In working with the children, Onyango became aware of gaps in their care.

Wilshire volunteers staff a medical clinic at the child development center in Busia 15 years ago.

“Yes, they could afford food because Buckner was supporting them, they could go to school, but there were emotional needs that were not being met,” she said. “I started going to school with the main purpose of understanding, ‘How do I equip myself? How do I get the tools necessary to take care of this child as well as the families from which they come?’”

Baylor School of Social Work connection

Onyango earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology and counseling in Kenya, and then in 2017 she began work on a master’s degree in social work from the Garland School of Social Work at Baylor University. She studied under a Global Missions Leadership scholarship that identifies community leaders in the areas of social work who have the potential to return to their communities and empower them.

As Coker was reconnecting with Onyango, he introduced her by email to Elizabeth Batuka, a student in his Global Perspectives in Missions and Ministry class at McAfee School of Theology in Atlanta. Both women were from Kenya, and both had master’s degrees from the Garland School of Social Work at Baylor. Coker thought that with so much in common, the two might enjoy getting to know each other. As it turned out, they needed no introduction: They were in the same cohort at the Garland School and, in fact, were roommates.

What happened to the kids

Today, Onyango lives in Nairobi, where she is manager of adoption services for Buckner Kenya. But she has maintained contact with some of the original CDC children through social media and in-person visits when she makes the 280-mile trip to Busia. Most completed school and have jobs and families of their own now. Some have gone on to college, shattering the barrier that keeps only 99% of Kenyans from high education.

Among the success stories:

-

Sharon today

Sharon lived with her maternal grandfather and was doing fine in school until she became pregnant. But with the support and counseling from the CDC, she delivered her baby and returned to school and graduated. Today the child is 8 years old and Sharon is a high school teacher.

- Sylvia had a rough time at home and in fact lived with Onyango for almost a year. She completed high school and got into a top university in Kenya where she completed a bachelor’s degree in business. She’s working on the Kenyan coast and doing well for herself and her younger siblings.

- Betty, Sylvia’s younger sister, is still in college and is training to work in the hotel industry.

Betty today

- Ezekiel earned a bachelor’s degree in information technology and is employed by Buckner Kenya in the IT department.

Onyango said the Busia program no longer focuses on individual children but instead works to support and empower entire families.

“We still have that kinship program or that community program, but right now the focus is more on the family unit and with a focus on empowerment so that the families can rise from poverty and be able to support their children,” she said.

Buckner Souls alumni group

Onyango said something remarkable happened as the Buckner program was shifting its focus from single children to families: Some of those first children helped by the CDC formed a group called Buckner Souls to provide extra financial support and other resources to young children in those families.

In a more recent photo, taken in 2018, children at Buckner’s child development center in Busia, Kenya, show off their new shoes.

“Buckner now has other child development centers in different towns, and the Buckner Souls have brought on board those who had been supported in the other Buckner programs,” she said. “It’s become more of an alumni group that now gives back to the Buckner efforts in supporting the younger kids.”

They have a Facebook page that explains: “Buckner Souls is a group of individuals who have gone through Buckner programs and were or are still beneficiaries of the projects. The main aim of the group was to help us come together as a family and unite in activities that include giving back to the society, community development, moral support to those who seem to have lost hope in life and general works of charity to help orphans, vulnerable children and families gain light and hope in their life.”

Many lives changed

Onyango counts herself among those who have been changed by the work in Busia.

“As much as we talk about the community program, I also look at myself as a beneficiary of that,” she said. “This is what actually pushed me into social work.”

Andrew Daugherty, now pastor of Pine Street Baptist Church in Boulder, Colo., was a pastoral resident at Wilshire 15 years ago and participated in the mission work in Busia, Kenya.

Onyango said Wilshire and other congregations that helped launch the child development centers in Kenya should be interested in what their efforts have created.

“I don’t see a farmer waking up in the morning to go to the farm only to sow seeds but they’re not interested in the harvest,” she said. “To me, what has become of this program really speaks of the investment and the time that was put into coming up with the programs that would benefit these children.”

She continued: “We do not just want to cast seeds and then never go back and see what actually became of those seeds. I think it’s good to hold organizations accountable and see what really became of the program, and in this case, what became of the children, how are they doing now. And that can also even help in terms of fundraising because many people desire to see the results.”

Onyango said that what has transpired in Busia continues to shape her own path and her destiny.

Leah Nekesa, who was a child when the Busia child development center began, show in her cap and gown at graduation.

“That’s what keeps me focused,” she said, “because when I see what those children have become — who probably at one point had no hope in life and maybe their family members have given up on them — when I see them blossoming today, having their own families, working, being able to support themselves and also support their families, it really encourages me to also keep working.”

And it should encourage churches that their contribution make a difference, Onyango said.

“It’s important, I believe, to at least understand that it was not in vain, it was not just wasted resources. Whatever it is, no matter how big or no matter how small, it played a huge role in the lives of these children. Because of those resources, they have been able to go to school and now they’re supporting others,” she said.

As for Coker, he is grateful for the rare look at the harvest.

“You don’t get that 15-year arc much, especially in the short-term mission world where things come and go and you never follow up,” he said. “But this was a church that made a commitment over probably five years to make sure what we started had a good footing, and it’s still going well independently of us, and the result is students who have made it against all odds.”

Jeff Hampton is a freelance writer based in Dallas.