While affirming bread-and-butter conservative issues on the first day of its annual meeting June 15, the Southern Baptist Convention turned back attempts at harder-line positions desired by the most conservative bloc of the body.

That included a narrow rejection of a presidential candidate backed by the Conservative Baptist Network, a group that had called for a second “conservative resurgence” in the SBC to root out perceived liberalism.

Messengers to the SBC annual meeting in Nashville, Tenn., also rejected a new business and financial plan proposed by the SBC Executive Committee, which has been accused of consolidating too much power and mishandling controversial issues. And they further slapped the Executive Committee by passing a resolution interpreting that only the convention in session — and not the Executive Committee — is the legal “sole member” of the various agencies and institutions of the convention.

More than 15,000 messengers — as voting members at the SBC are called — registered on the first day of this year’s convention, making it the largest annual gathering in 25 years. It also lived up to expectations as being one of the most controversial of the past two decades.

Presidential race

In a four-way race for the convention’s presidency — a one-year term that can be renewed if elected to a traditional second year — messengers chose a candidate billed as a uniter and healer.

While Litton was presented as a unity candidate, Stone ran as a purity candidate.

Ed Litton, pastor of Redemption Church in Saraland, Ala., was chosen over Mike Stone, pastor of Emmanuel Baptist Church in Blackshear, Ga.; Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary; and Randy Adams, executive director of the Northwest Baptist Convention.

Litton was nominated by Fred Luter, pastor of Franklin Avenue Baptist Church in New Orleans and the first and only Black person to serve as SBC president.

Saying the SBC has “reached a tipping point” with declining membership numbers and baptism numbers, as well as declining trust in each other, Luter said Litton is a “uniter” who has “uniquely shown his commitment to racial reconciliation.” Litton also “brings a compassionate and shepherding heart,” he added.

In the first round of voting, Litton and Stone rose to the top and were sent into a runoff. In the initial ballot, Adams received 4.71% of the vote, Mohler received 26.32% of the vote, Litton received 32.38% of the vote, and Stone received 36.48%. SBC bylaws require a candidate to receive more than 50% of the vote to be elected.

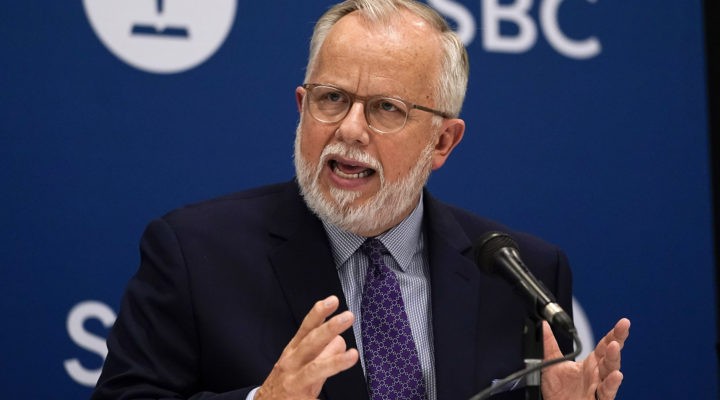

Mike Stone (Baptist Press)

On the second ballot, Stone received 47.81% of the vote and Litton 52.04%. However, the actual gap between the two was 556 ballots.

While Litton was presented as a unity candidate, Stone ran as a purity candidate. He was billed by the Conservative Baptist Network as someone who would hold the line against any and all forms of liberalism or accommodation to culture.

Stone was nominated by Dean Haun, pastor of First Baptist Church in Morristown, Tenn. Haun compared Stone to the biblical character David standing up to the giant Goliath.

“We need a champion who will go into battle believing in the authority and sufficiency of Scripture,” he said, adding that Stone has a “stainless steel backbone.”

Prior to the convention, Stone had come under fire for his recent role as chairman of the SBC Executive Committee, where he was accused of blocking attempts to respond to the problem of sexual abuse in the denomination. Stone was particularly singled out by Russell Moore, who recently resigned as head of the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, as one of his chief tormentors. Stone led a highly controversial Executive Committee investigation of Moore and the ERLC.

Rebuke of Ronnie Floyd

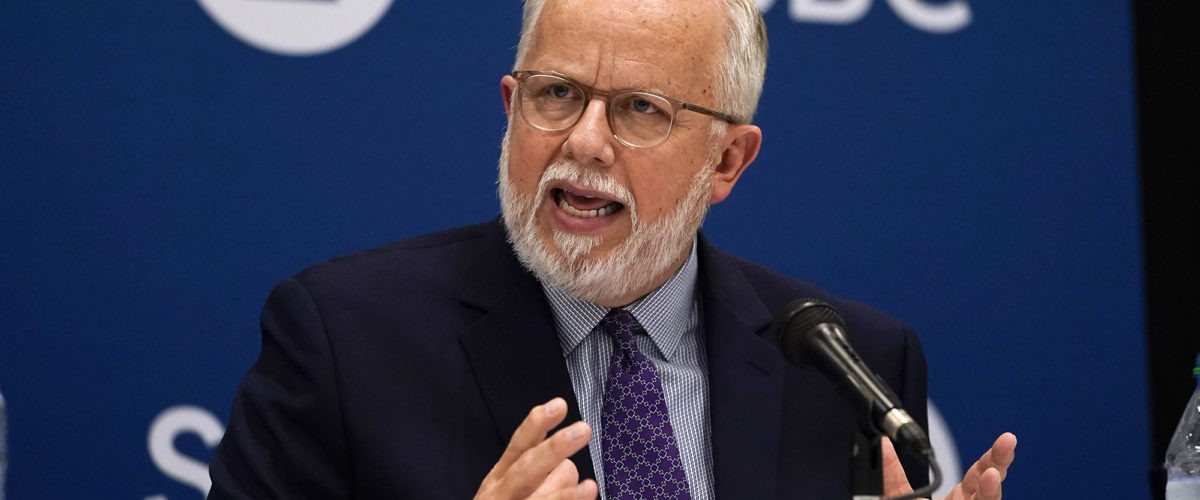

Stone’s defeat as a presidential candidate paralleled several hard blows against the Executive Committee and its top staff leader, Ronnie Floyd — himself a recent two-time SBC president.

Messengers’ overwhelming rejection of the proposed business and financial plan was a serious blow to Floyd, who has served as president of the SBC Executive Committee only two years.

And although messengers did approve a Vision 2025 plan crafted by Floyd and the Executive Committee, they first amended it to include a new objective not in the Executive Committee’s draft: “That we prayerfully endeavor to eliminate all incidents of sex abuse and racial discrimination among our churches.”

That amendment was proposed by messenger Benjamin Cole of Plano, Texas, who has been a frequent and vocal critic of Floyd’s leadership. Cole is a Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary graduate who now works as a crisis communications consultant. He also blogs anonymously as “The Baptist Blogger.”

Ronnie Floyd (Baptist Press)

Cole penned an opinion piece for Religion News Service that ran June 15, in which he said Floyd is in over his head as the top paid leader of the SBC.

“On Floyd’s watch, the 15-million-member SBC has been convulsing and hemorrhaging from a series of self-inflicted wounds and circular firing squads,” Cole wrote, later adding that Floyd “represents a dying good-ole-boy network that’s resistant to transparency and accountability.”

He concluded: “To many, including some of his peers, Floyd is seen as the proverbial dog who caught the car: He finally got the job he always wanted and doesn’t know what to do with it.”

While multiple motions and resolutions made at the convention on Tuesday took aim at Floyd and the Executive Committee, some messengers praised Floyd and the committee. Among those was Malachi O’Brien, pastor of The Church at Pleasant Ridge Harrisonville, Mo. O’Brien spoke in favor of adopting the Executive Committee’s new strategic plan and called Floyd “the greatest leader I’ve ever known.”

For his part, Floyd introduced the Vision 2025 plan with a fiery sermon about the perils of a literal hell, drawn from the book of Revelation.

He spoke of a literal lake of fire, “eternal and everlasting separation from God,” and “eternal and everlasting torment and punishment” as motivation for the SBC to adopt his new strategic plan. “An eternal lostness exists, and eternal hell is waiting. So we must do all we can to reach people so their names will be written in the Lamb’s book of life.”

Rejection of business and financial plan

Messengers’ rejection of the new business and financial plan put forward by Floyd and the Executive Committee was a rare example of an SBC entity proposing a detailed plan not adopted by the convention in annual session.

Two of nine recommendations presented by the Executive Committee were voted down, and a third was later declared moot because of those actions.

Recommendation 7 would have granted the Executive Committee more oversight in order to “strengthen the financial accountability” of SBC entities and would have allowed the Executive Committee power to escrow Cooperative Program funds from any entity not complying with a 10-point checklist.

Rolland Slade, chairman of the SBC Executive Committee, presents the committee’s report to the SBC annual meeting June 15. (Photo: Baptist Press)

The six SBC seminary presidents even opposed the plan, as illustrated by Southeastern Seminary President Danny Akin, who went to a microphone to oppose it. His comments were met with applause and whistles from messengers.

“I am chair of the Council of Seminary Presidents and speak on behalf of all six of us opposing this recommendation,” he said. “This would jeopardize our standing with our accrediting agencies … because they already wonder about oversight. They ask, how does this keep outside interference? And we always say the money comes from our churches who hold us accountable through our trustee system.”

Vance Pitman, pastor of Hope Church in Las Vegas, also opposed the plan: “This proposal would be an unprecedented expansion of the Executive Committee’s powers and would put itself between the local churches and the entities we are trying to support with the Cooperative Program.”

Also rejected was a proposal to amend the 10 ministry assignments given to Lifeway Christian Resources. Among those was a plan to transfer responsibility for college student ministry from Lifeway to the North American Mission Board.

Strongly worded resolutions

Any doubt that the SBC has gone soft on key doctrinal and cultural issues was laid to rest by the report of the Committee on Resolutions, which put forth 10 nonbinding resolutions addressing abortion, race and sexuality among other topics.

The resolution on abortion was not strong enough for some messengers.

However, the resolution on abortion was not strong enough for some messengers, with a supermajority of two-thirds approving a mandate that the resolutions committee bring forth on Wednesday a second resolution on abolishing abortion in America. The committee had declined to advance that resolution and instead focused on what it considered a combined statement on abortion and the Hyde Amendment.

Under SBC processes, messengers are allowed to submit proposed resolutions well in advance of the annual meeting, although resolutions acted on by the convention must come from the committee.

A listing of every name of someone who submitted a resolution to the committee ran across five pages of the Tuesday Bulletin at the convention and included hundreds of names.

Most resolutions advanced by the committee received considerable debate and multiple attempted amendments on the floor. Despite tensions in a crowded and hot room at the Music City Convention Center, most messengers attempted to demonstrate good humor as they made their points. President J.D. Greear, who presided over the resolutions debates, set the tone with his own cordial approach and occasional humorous comments.

A resolution on “Baptist unity and maintaining our public witness” encouraged messengers to “pursue holiness, act with the aim of love, engage others with charity, and consider one another in how we represent ourselves, our churches, our convention, and, above all, the gospel of Jesus Christ in our speech and conduct at all times and in all places.”

That desire and the overall good humor of the body was tested at several points during debate on resolutions.

Resolution on race

The first flare-up came during debate on a resolution titled “On the Sufficiency of Scripture for Race and Racial Reconciliation.”

Several messengers had submitted resolutions seeking to rescind a 2019 SBC resolution that allowed the use of Critical Race Theory so long as it was not understood to contradict Scripture or the SBC’s doctrinal statement, the Baptist Faith and Message. Soon after, then-U.S. President Donald Trump issued a broadside against Critical Race Theory and all forms of diversity training in the university or workplace. SBC leaders quickly followed suit, and Critical Race Theory became a hot topic from the pulpit and in Baptist conversations.

An overhead view of the exhibit hall at the SBC annual meeting in Nashville. (Baptist Press)

When the six SBC seminary presidents in late November 2020 came out with a strongly worded statement denouncing Critical Race Theory, they faced a firestorm of protest from Black pastors, many of whom see this academic construct as a helpful way to highlight systemic racism.

Thus, this year’s Resolutions Committee attempted to craft a resolution about Critical Race Theory without using those words. The resolution as presented affirms “our agreement with historic, biblically faithful Southern Baptist condemnations of racism in all forms” while rejecting “any theory or worldview that finds the ultimate identity of human beings in ethnicity or in any other group dynamic.”

It further rejects “any theory or worldview that sees the primary problem of humanity as anything other than sin against God and the ultimate solution as anything other than redemption found only in Christ.”

That was not enough for some messengers, who opposed the resolution outright or hoped to amend it before it was adopted.

Kevin Apperson, pastor of North Las Vegas Baptist Church in Nevada, spoke against the resolution, saying its language was “ambiguous” and “unclear.” He said the resolution appeared to be about Critical Race Theory without ever calling it by name.

He opposes Critical Race Theory, he said, because it is “an ideology that tells me I am inherently guilty because of the melanin content of my skin.”

“If we do not have the courage to call a skunk a skunk, let’s not say anything.”

“Two years ago, we approved Critical Race Theory as a teaching tool, and now we need to address it by its name,” he said. “If we do not have the courage to call a skunk a skunk, let’s not say anything.”

This drew a sharp and impassioned retort from James Merritt, a Georgia pastor who is a former SBC president and this year’s chairman of the Resolutions Committee. He portrayed debate over this resolution as a marker for which mentality within the convention will prevail — evangelism or legalism.

“It’s time to find out who we are and where we’re headed,” he said. “I want to say this bluntly and plainly. If some people were as passionate about the gospel as they are about Critical Race Theory, we’d win this world to Christ tomorrow. … Let’s just settle this issue once and for all. … We reject any theory that says the problem is anything other than sin and the solution is anything other than salvation. … There’s a world watching out there. This is exactly what they want …. Let’s give ’em something to talk about. We can either build bridges and tear down walls or we can build walls and tear down bridges.”

After Merritt’s speech, another messenger called the question, and the resolution was adopted as written.

Resolution on abortion

The committee’s proposed resolution on abortion — a favorite topic of SBC revolutions over many years — couched its language around support for the Hyde Amendment, a 1976 federal policy preventing tax dollars from being used to pay for abortions or health benefits that include coverage of abortion.

In its budget proposal to Congress, the Biden administration has proposed eliminating this amendment, which the resolution decried as “advocating to make taxpayer money available to fund abortion procedures.”

The resolution classifies “any effort to repeal the Hyde Amendment as morally abhorrent, a violation of biblical ethics, contrary to the natural law, and a moral stain on our nation.”

And then it concludes with an assertion that the SBC “should work through all available cultural and legislative means to end the moral scourge of abortion as we also seek to love, care for, and minister to women who are victimized by the unjust abortion industry.”

That last paragraph drew critique from Josh Rice, associate pastor at Reformation Baptist Church in Centerton, Ark. He sought to strike the words “love, care for, and minister to women who are victimized by the unjust abortion industry” with “preach the gospel and urge repentance from all men and women guilty or complicit in the sin of abortion.”

While grateful for the resolution and sharing its support for the Hyde Amendment, Rice said the language about women being victimized “interferes with the gospel by softening sin and, therefore, eliminating the ability of the law to tutor the need for confession and repentance.”

“Women who obtain abortions, although their situation may be tragic and horrible, they are by the law murderers.”

He added: “Let me be clear. Women who obtain abortions, although their situation may be tragic and horrible, they are by the law murderers, and, therefore, should seek repentance and we should not be so arrogant to presume that their circumstance excuses their need for salvation from their sins.”

Committee member Dana Hall McCain of Dothan, Ala., spoke passionately and emotionally in response to Rice’s proposed amendment. She spoke of her own work counseling pregnant women who are considering abortion.

Dana Hall McCain speaks to a proposed amendment on Resolution 3 during the 2021 SBC annual meeting June 16. (Baptist Press)

“Before I entered into that task, I would have been very tempted to adopt language more in line with what you just proposed, and so I sympathize with the position that you hold,” she said. “However, what the Lord has shown me sitting in those rooms across from broken women is that so many of them have been victimized by the sin of others, by generational sin, by parents who never took them to church and preached the gospel to them the way mine did to me.”

She added: “Yes, abortion is sin. … But I am also telling you that when we take a punitive and hard-hearted position toward women who are at a crossroads that usually a whole lot of people’s sin brought them to, we are not having the mind of Christ toward those women.”

The amendment was defeated, and the resolution was adopted.

Resolution on LGBTQ inclusion

This year’s resolution against the LGBTQ community took the form of opposing the Equality Act, a piece of anti-discrimination legislation currently before Congress. It labels same-sex attraction a “sin” and quotes previous SBC resolutions on sexuality and gender.

“God’s design was the creation of two distinct sexes, male and female …, which designate the fundamental distinction that God has embedded in the very biology of the human race,” it declares. And: “The Bible gives us clear instruction and boundaries with regard to what constitutes God-honoring expression of human sexuality.”

This resolution drew several amendments, most of which were accepted by the committee as friendly amendments. All the amendments sought to insert more restrictive language than the committee had proposed.

Jared Moore of Crossville, Tenn., asked that the phrase “sexual orientation or gender identity” be changed to read “sexual or gender identity,” eliminating the word “orientation.”

“When we use language like ‘sexual orientation,’ we imply no possible culpability as if this is something that happens totally regardless of one’s will,” he said. “And that’s what the culture means when they use this language. Instead, I have suggested that we change it to ‘identity,’ which when we are sharing the gospel, we are talking about our identity being in Christ, and God gets the last word about changing people.”

“I added heterosexuality because it is the only sexuality designed by God according to Genesis 2.”

He also proposed changing a phrase about “God’s good design in sexuality as clearly expressed in Scripture” to substitute the word “heterosexuality” for “sexuality.” His reasoning: “I added heterosexuality because it is the only sexuality designed by God according to Genesis 2.”

The committee accepted his amendments.

The committee also accepted a proposed amendment by Byron Talbot of Athens Tenn., who added this phrase: “and invite all members of this community to turn from their sins and trust in Christ and to experience renewal in the gospel.”

The committee also accepted an amendment offered by Andrew Walker of Louisville, Ky., naming professionals who are not clergy but would be “wrongly targeted by the Equality Act.”

Resolution on spiritual abuse

More debate ensued over a resolution titled “On Abuse and Pastoral Qualifications” that was the Resolutions Committee’s response to concerns about sexual abuse in SBC churches.

Noting that Scripture commands that pastors are to be “above reproach” and “blameless,” the resolution declares that “any person who has committed sexual abuse is permanently disqualified from holding the office of pastor.”

While no one rose to object to the intent of the resolution, some messengers questioned the language and the broad brush of the resolution.

Mike Hibbard, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Fulton, Mo., said he agrees with the intent and abhors “any sort of abuse, especially sexual abuse.” But a permanent disqualification “does not regard God’s transformational power and forgiveness. This comes dangerously close to compromising the autonomy of the local church.”

Likewise, Phillip Bramblett of Rocky Mount, Va., said he is himself a victim of sexual abuse as a child but thinks the language of the resolution is too broad. “I hate sexual abuse as much as anyone, but we shouldn’t elevate it to a sin (that is unforgivable). This resolution is too blunt.”

After additional debate, the resolution was adopted as presented by the committee.

Related articles:

Outgoing SBC president affirms conservative values while decrying legalism