Evangelical Protestantism continues to be a growing force in American Christianity, as Mainline Protestant denominations continue to decline, but where are these converts coming from?

There is very little data showing where Christians go when they convert away from a tradition or denomination. However, it is possible to track overall group trends. The Southern Baptist Convention, Presbyterian Church USA, Episcopal Church and other large denominations keep strenuous data on membership and attendance. Other groups like the Anglican Church in North America provide data that can be extrapolated.

What is not available — and is a huge missing piece — is comparable data from nondenominational churches.

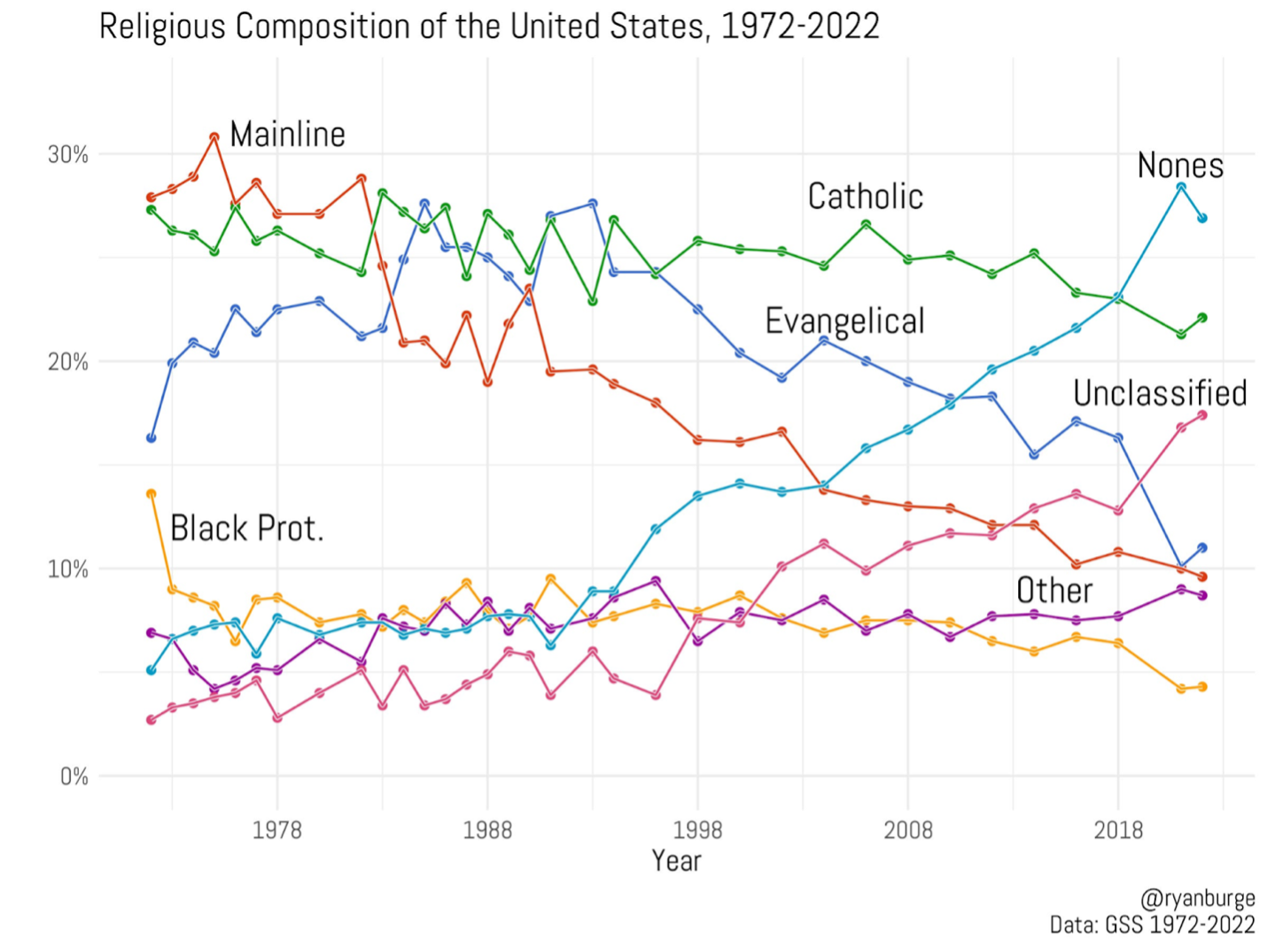

Two segments of the American religion market are growing today: evangelicals (as a general category) and “nones,” meaning those who are not religiously affiliated and now make up the largest religious category in America.

“Evangelical” can mean many things, depending on the study’s definition. It can simply mean those who identify as “just Christian,” “born again” Christians, low-church fundamentalist-leaning denominations, contemporary megachurch culture, or denominations with a decidedly conservative bent.

However, the well-defined category of Mainline Protestantism is shrinking and evangelicalism, broadly defined, is not. But even that statement is complicated.

Evangelical growth

Religion researcher Ryan Burge says the death of evangelicalism is a myth, although that case can be made through selective data.

“If you’re an atheist or agnostic, you want to start the graph at 1994,” he told Religion News Service in 2022. “From that it looks like a decline — that evangelicals are free falling. But if you’re an evangelical, you look at the graph from when the data started in 1972, and you see it actually might be up a little bit from 1972 to today. There were more evangelicals, both by percentage and by raw numbers, in 2020 than there were in 1972.”

The same cannot be said for Mainline churches, Burge says: “Mainline Protestantism and liberal Catholicism are in an absolute free fall right now, but devout, conservative religions are doing well by comparison and actually might be growing over time. So conservative religion is up and secularism is up, and there’s not a whole lot left in the middle.”

Mainline churches are the Congregational Church, the Episcopal Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church, the Presbyterian Church, the United Methodist Church, the American Baptist Convention and the Disciples of Christ. In 2007, 18.1% of Americans identified as members of Mainline churches, but that decreased to 14.7% by 2014.

The Southern Baptist Convention, various Black Baptist conventions, the Church of Christ, Adventist and Pentecostal churches stand apart from the Mainline label and most often get classified as evangelicals.

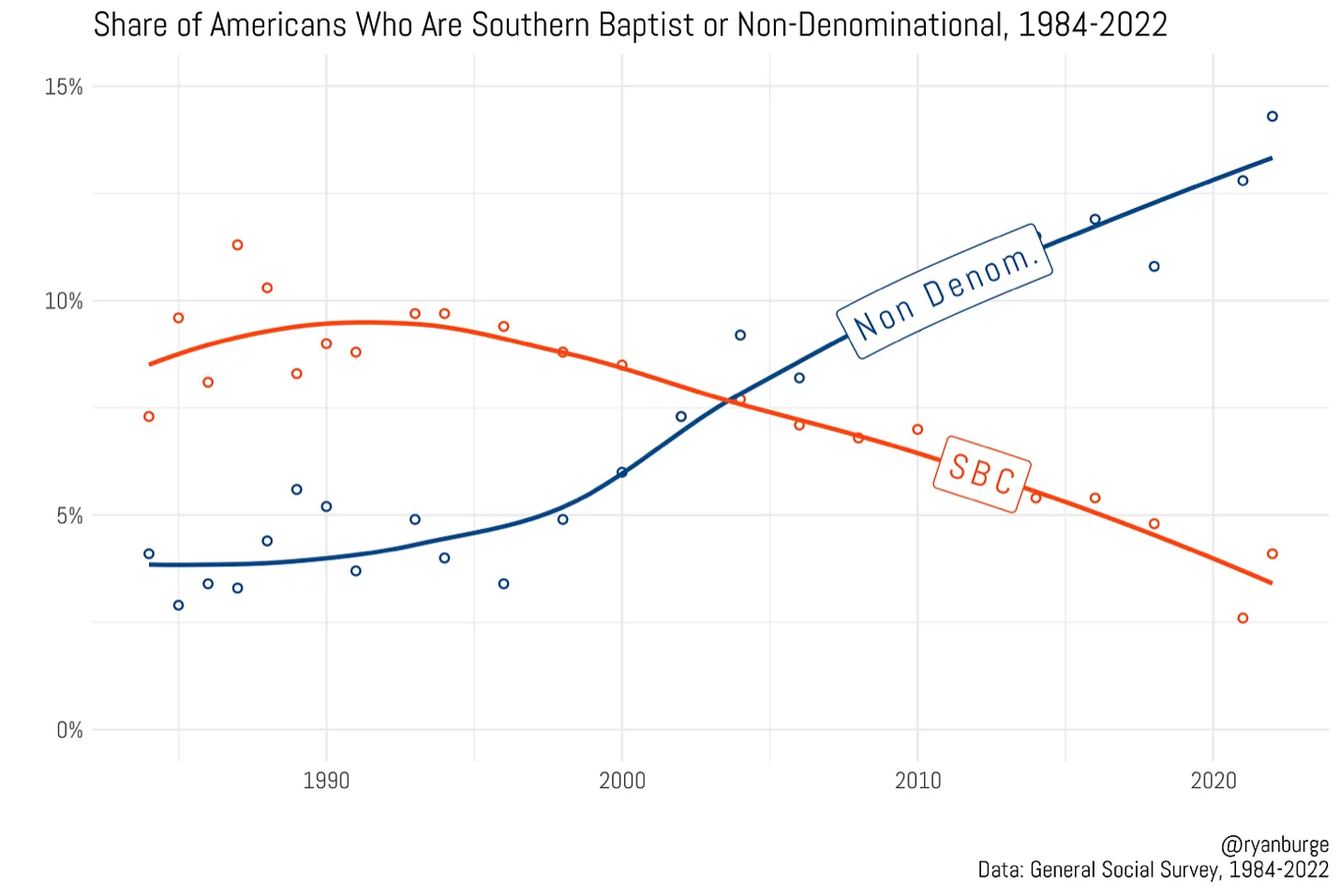

Yet one group that does not fit the labels and trends is the SBC, which is evangelical in nature but as a denomination has been in statistical freefall for two decades.

It is likely that decline in the SBC is part of the same story as the growth of nondenominational churches. Not all the conversions happening at nondenominational churches are first-time commitments of faith and baptisms.

Who’s converting and why?

Not only has evangelical Protestantism overtaken Mainline Protestantism in recent decades, but nondenominational Protestantism has overtaken the evangelical category. In every major city in America — and even in rural crossroads communities — nondenominational churches have sprung up. Many have become megachurches.

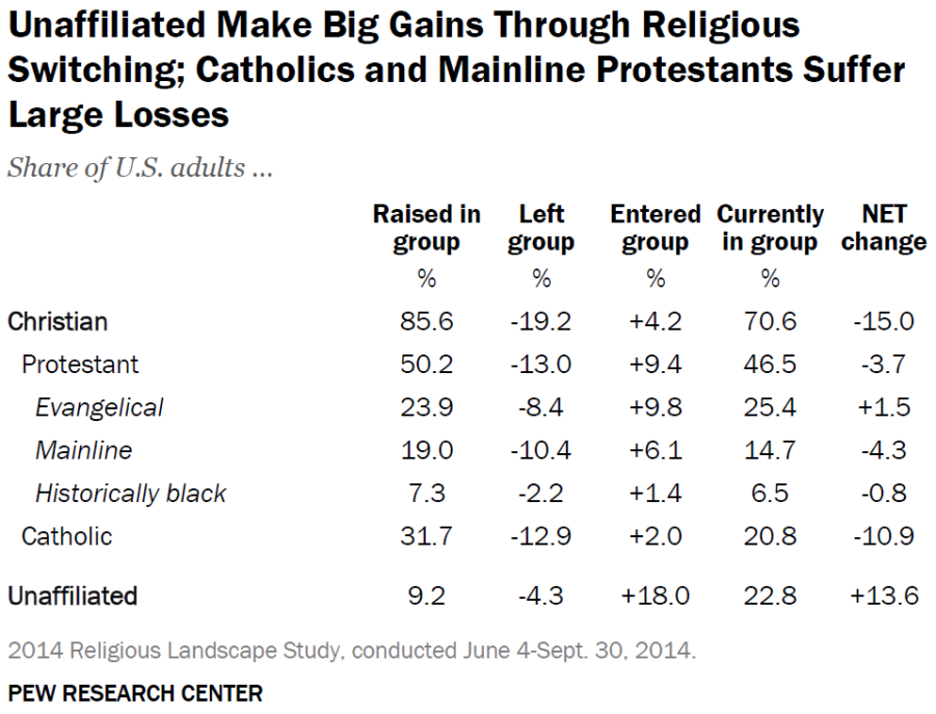

Pew Research notes that 42% of Protestants swapped between Mainline Protestantism, evangelical Protestantism, historic Black Protestantism or other religions between 2007 and 2014.

“Nondenominational Protestants … gain more adherents through religious switching than they lose,” Pew reports. “Just 2% of Americans say they were raised as nondenominational Protestants, and half of them (1.1% of all adults) no longer identify with nondenominational Protestantism. But 5.3% of adults now identify as nondenominational Protestants after having been raised in another religion or in no religion.”

Survey any nondenominational megachurch in the American South and you’ll find a lot of former Southern Baptists there.

Survey any nondenominational megachurch in the American South and you’ll find a lot of former Southern Baptists there.

Lifeway Research reports there are many reasons Protestants and evangelicals swap denominations and churches. The most common cause is simply when people move and seek new churches. Unlike 30 years ago, when a Southern Baptist moved and sought another Southern Baptist church.

“Church swapping” remains relatively uncommon among adults. However, people may leave their churches because something changes (29%), it is unfulfilling (29%), or they become frustrated with the church leaders (27%) or with the church itself (26%), Lifeway says.

Lifeway found 22% of those who leave do so over political or doctrinal disagreements. Among this group, 28% found their church leaders too liberal and 23% found them too conservative.

Another factor is young adults raised in a particular Christian tradition who go out on their own and move to another tradition that better suits their own beliefs rather than the beliefs of their parents.

The net of all these various changes is a steady decline in the SBC for the past 18 years, from a peak of 16.3 million members in 2006 to 12.98 million in 2023.

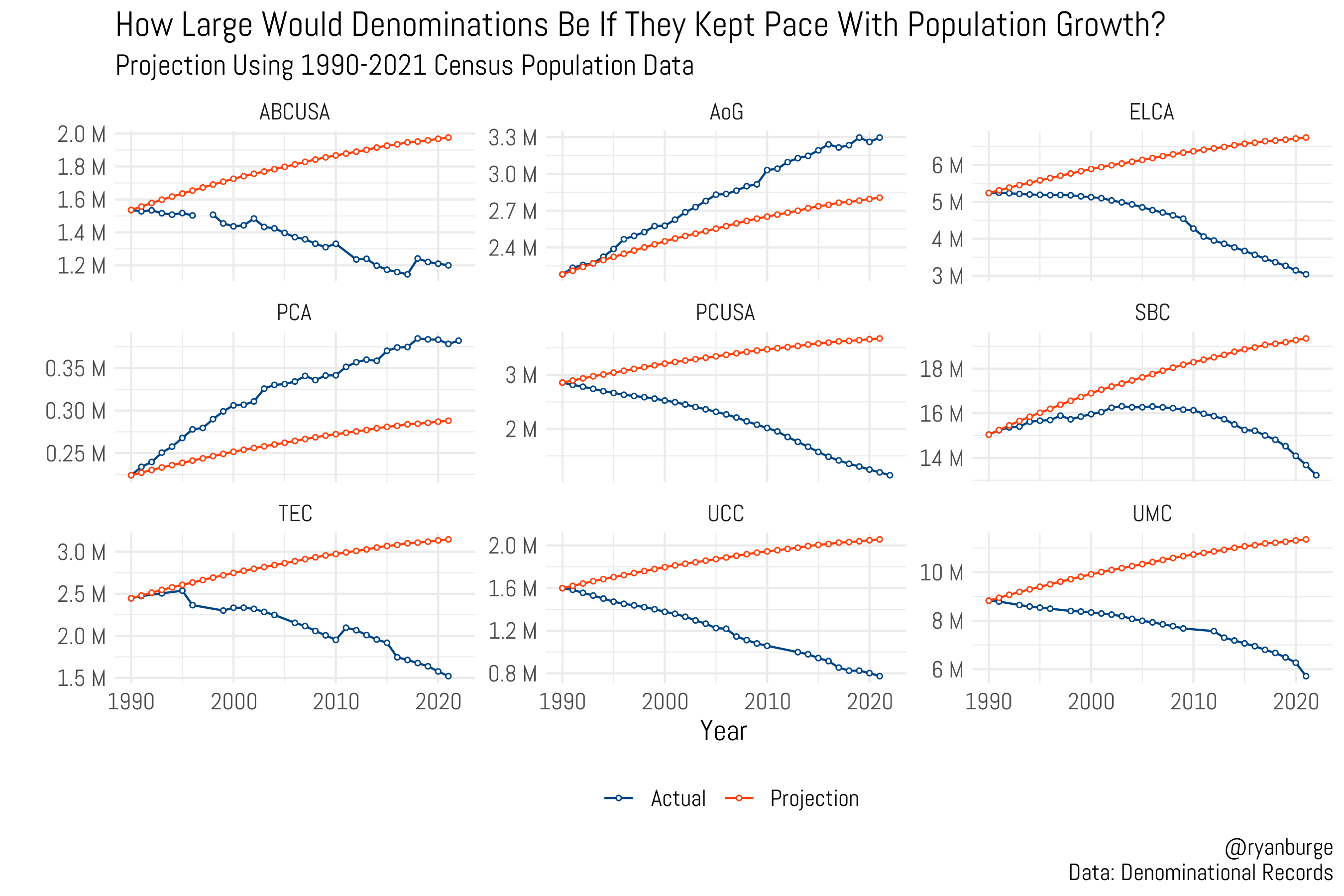

And that’s not accounting for market share as the U.S. population has grown. Burge has documented that only the Assemblies of God and the Presbyterian Church in America have outpaced population growth, meaning they are growing faster than the natural increase in the population. Everyone else among the Mainline and the SBC is going the opposite direction.

Once again, the biggest winner in all this is the nondenominational churches. According to the General Social Survey, nondenominational Christians overtook the SBC in the mid-2000s and are significantly outpacing the nation’s largest Protestant denomination.

Christianity Today reports: “The number of nondenominational churches has surged by about 9,000 congregations over the course of a decade, according to new decennial data released by the US Religion Census. Little noticed, they have been quietly remaking the religious landscape.”

CT adds: “There are now five times more nondenominational churches than there are Presbyterian Church (USA) congregations. There are six times more nondenominational churches than there are Episcopal. And there are 3.4 million more people in nondenominational churches than there are in Southern Baptist ones.”

To quote Burge, who’s also an American Baptist pastor, “The future of American Christianity is nondenominational.”

New evangelical denominations

There’s also evidence that newer evangelical denominations like the Anglican Church in North America and Presbyterian Church in America, both founded in opposition to political and doctrinal trends in the Mainline, are picking up displaced evangelicals.

The ACNA has grown from 103,090 members in 2013 to 124,999 in 2022, while the PCA has grown from 383,721 members to 393,528 in the past five years.

This isn’t entirely from Mainline conservatives jumping ship, but more likely wholesale conversions from other denominations like Baptists and nondenominationals.

The Living Church notes the ACNA’s data suggests the majority of its congregants aren’t former Episcopalians: “The figures suggest that the ACNA dioceses largely composed of ex-TEC parishes have tended to plateau or shrink.”

Additionally, the ACNA has seen notable growth in areas like the Midwest, which had limited Episcopalian outreach before the ACNA’s founding.

“In 2009, it was largely defined by being ‘ex-TEC.’ Now, many members and congregations have no memory of being part of TEC,” The Living Church explains. The growth is happening in new church plants.

“The Anglican Church in North America (is) attracting larger numbers of people who do not have an Anglican and Episcopal background and therefore have an even greater likelihood of not having any exposure to historic Anglicanism,” says Anglicans Ablaze. “The data tell us that the Anglican Church in North America is growing. What the data do not tell us is how much of the ACNA’s growth is transfer growth and how much of its growth is conversion growth.”

Researchers offer an important caveat to all this data: The decline of Mainline denominations cannot entirely be attributed to the rise of evangelical alternatives.

As Burge notes, the “PCA is still incredibly small. The Southern Baptist Convention lost more members last year than the entire membership of the PCA. So, it cannot, in any meaningful way, fill the gap.”

And this from Pew Research: Of those converting away, a quarter of people raised Mainline end up switching to religiously unaffiliated, also known as the “nones.”

Why is Mainline Protestantism dying?

The split between Mainline Protestantism and evangelical Protestantism has been lengthy, going back to the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy of the early 20th century. The divide has only widened into an irreparable schism.

While American religiosity has radically decreased — with 90% of Americans in 1972 identifying as Christian compared to 63% in 2022 — the split between theological conservatives and liberals has proved equally substantial.

The continued schism of the Mainline has aided this decline. Several evangelical-leaning denominations have arisen in recent years amid internal disagreements in larger denominations.

In 2009, the ACNA was founded, taking at least 21,808 members of The Episcopal Church with it. In 2022, the Global Methodist Church was founded by former members of The United Methodist Church in protest of issues such as same-sex marriage and the ordination of noncelibate gay ministers. A quarter of U.S. Methodist churches have left the denomination in the past five years.

Existing smaller denominations like the Reformed Episcopal Church, the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod and the PCA also have seen nominal gains from Mainline Protestants seeking evangelical options. In the LCMS, that has only moderately reduced its ongoing decline.

Despite their losses, Mainline denominations remain much larger than their evangelical counterparts.

Despite their losses, Mainline denominations remain much larger than their evangelical counterparts, with The Episcopal Church (1,584,785), PCUSA (1,140,665), United Methodist Church (5,424,175), and ELCA (2,904,686) having more members than the respective ACNA (124,999), PCA (393,528), Global Methodists (no data), and LCMS (1,433,378).

But the trends cannot be ignored.

Burge explains: “There were 6.3 million United Methodists in 2020. The best estimate of their current number is 4.9 million. That’s a decline of 1.4 million during the same time period, representing a percentage decrease of 21% since 2020.”

The majority of these traditional American denominations are aware they are staring down a statistical cliff: One researcher suggests The Episcopal Church will cease to exist by 2050. Even the SBC, if current trends continue, will run out of members within the lifetime of today’s young adults.

The Assemblies of God is the only Mainline church bucking trends and seeing growth, due in part to its connection to the growing Pentecostal movement.

From a political perspective, the only churches stable in membership or growing tend to have members who are more conservative. Which is why New York Times reporter Ross Douthat suggested in 2017 that America’s changing religion demographics could reflect Christianity’s rightward push.

“The wider experience of American politics suggests that as liberalism de-churches, it struggles to find a nontransactional organizing principle, a persuasive language of the common good.”

That led economics researcher Lyman Stone, a Lutheran, to join Douthat in this conclusion: Liberalism itself might be put on a stronger intellectual and social footing if it reembraced churchgoing.”

And all this conversation involves a minority of the American public today. Gallup notes that only 30% of Americans say they attend religious services every week or almost every week (9%), while 11% report attending about once a month and 56% say they seldom or never attend.